September 17, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

I want to start off this post with a definition–two definitions or really, a distinction. Writers and critics often talk about the responsiblity of the artist, what things we should and should not do and how, and as I’ve said in the past, I’m not too fond of burdening creative people with an intent of social justice. (This is not to say art doesn’t provide moral instruction: It is more so that art presents a multitude of moral possibilities and shouldn’t serve merely as propaganda.) That tends to be a recipe for didacticism rather than enlightenment. However, I do think that art itself is meant to do one thing: It shows the world as it is, as the writer sees it. Now I know that may sound absurd, especially when we take into account the many genres available to us. How does the fantasy or sci-fi writer depict the world as it is, when the story takes place in an entirely different universe? Well, the story, no matter the species or world, should connect to those experiences we all share as human beings. There are flaws in human nature, things we don’t like about ourselves as much as there are many strengths. Neither will ever be exitinguished. Societies, even those that appear utopian, still give into our failings. That’s what makes stories worth reading. But if, instead, we depict the world as we want it to be, as we’d like it to be, we begin to tap into something else: pornography. You see, pornography, to me, is not just something that excites or titillates us, but shows us a world we’d like to inhabit. Have you ever watched a porn? Depending on your own personal fetish, you are the viewer of your own particular fantasy. Do you wish women would fawn all over you and decide to have sex with you in moments of meeting you? Do you wish your man would massage you and spend a lot of time on foreplay? Whatever it is that turns you on is there with a few clicks of the mouse. But the world doesn’t operate under those conditions. Our lives are not fantasy, and if you want to see your perfect world in art, you’re only engaging in masturbation.

#

I can’t remember the name of it, but a few years ago a book came out that depicted a homosexual love story in a very conventional way, in the sense that it was merely about two gay people in love with one another. I do not know whether the novel was very good or not, but that’s besides the point. There were two camps of people who had two very different reactions. First, there were the supporters, who felt that the novel was a good one and found it refreshing that the novel didn’t concern itself the societial struggles of the couple. It was just a love story where the characters happened to be gay. The other side thought the novel avoided the issue, that it should have been a main theme of the book. My problem is with the latter group. Who says that the characters have to face the structural oppression of their culture? Can’t they face other challeges? The story is about their love. The writer’s experience and knowledge is what dictated the focus of the narrative, not his or her political agenda. I’m sure the writer is for equality, and if he or she is gay, they are tapping into their world as it is. Does being gay change the governance of a story? Does it mean that the structure must be completely different? Do the characters have to act a certain way? We seem to want to straddle this line of categories are important/unimportant, that we are unique and also part of a group. But if our characters can’t represent that unique perspective, then doesn’t that make for fiction that is largely the same?

#

One of the best movies to come out in a while is Mad Max: Fury Road. It’s brilliant in its construction and reminded us how exciting (and visual) films can be. It’s also one of the most feminist films I’ve seen. Furiosa could have easily been one of those hard-nosed, masculined female characters, the kind that fuck but can’t connect to people. She, however, is Max’s kindred spirit: She is his equal in almost everyway. There are some things Max is better at, like killing a bunch of guys in the fog, but she’s a better shot and driver. They work together in perfect harmony. They’re both sensitive and caring, even when they know they shouldn’t be. And really, if Max wasn’t a crazy drifter, I would even think that the two of them would have been more than happy to start a physical relationship to add their emotional one. They play off one another and serve each other’s stories, helping one another to find redemption. That’s pretty rare on-screen or off.

Unfortunately, we have a lot of narratives that don’t do this–and it’s not because of institutional sexism as so many critics claim. It’s because they’re poorly written, and somehow we’ve forgotten this. (Art is really, really hard. Writing even an essay is strife with traps. It’s hard enough to convey an idea through argument and evidence. When you add story, it gets that much harder. Most of the time, people don’t know what the fuck they’re trying to say with their art.) To me, lovers in any story must be equals; otherwise, what’s the point of putting them together? Han and Leia in Empire and even Jedi are a terrific example. Once their initial courtship ends, they face challenges together. They aren’t spending their time quibbling about stupid shit. They have a mission, and it’s one they attack as a couple. Sure, they might squabble over how best to do it, but they still end up working together as a team.

One thing I find particularly frustrating, in television mostly, is when the writers wedge problems into the relationship–especially after seasons of will-they-or-won’t they. Why is it that these couples end up bickering in the subplot? Sure, relationships aren’t perfect, but why waste my time with something that shouldn’t be a problem? The goal is achieved. Turn your attention elsewhere. The next goal isn’t making things work: It’s taking on the new challenge or challenger as a team.

#

I read an article just recently that says that “Female characters often aren’t allowed to have their own story arc.” I’m not fond of this particular generalization. I can think of few good stories where this is the case. Every character wants something, and by the end of the story, that character should either succeed or fail. In Die Hard, Holly Gennaro wants to be a successful business woman, and she thinks that means she has to sacrifice her relationship with her husband. They, of course, have to put those martial problems aside in order to stop the terrorists, which they do as a team. In the end, she recognizes that they can be together, and presumably, doesn’t need to distance herself from her husband in order to be a success. In Batman Begins, Rachel is Batman’s conscience–and has her own strategy to achieve their common goal. In Iron Man, Pepper Potts primary goal is to keep Stark Industries running. The love stories aren’t tacted on: They’re integral to the story because a good writer knows they should never put something in that doesn’t serve a purpose. But there are plenty of writers who don’t recognize this, and that’s just what the author of that article is inadvertently complaining about. It’s not a gender issue. It’s quality control.

#

Critics say we need more “strong female characters” in art. First, what the hell is a strong character? When I hear it described, what it sounds like is a complete character, one who is complex and real, but people tend to take this as “women need to be badass.” I object to that as much as I do the term “strong female character” for its inaccuracy.

Just about every movie nowadays that has a squad of soliders needs to have that badass female in it. Those characters tend to be as one-dimensional as the rest of the squad. So really, what’s the point? Characters in the background are just scenery. Ripley is complete; Vasquez is just a diversity credit. It doesn’t matter what those ancillary characters are or do, really. If you want a “strong female character,” they can’t come from the background. I think we should recognize that there’s little benefit to making some tertiary or quaternary character a woman, a person of color, a homosexual. How do you characterize this minor player? How can you get your reader to know who they are in the paragraph or two in which they appear? Do we have a shorthand to solve this? We do. They’re called stereotypes.

#

So what makes a “strong” character strong? The answer should have started to reveal itself by now. A strong character is our focal center: It is the protagonist. No other character can compare to them, except maybe the antagonist or love interest or best friend. You can’t render every character as completely as you would like.

And how do we remedy this situation? Obviously, we need more characters of certain categories, but who should create them? Should we burden the predominate writing population (read as white, cis, heterosexual males) with the solution? It might seem blasphemous, but I say no. Critics quibble with any act an author makes, binding them to a strict biological essentialism. They say a writer’s female or ethnic characters are stereotypes or that they’re writing about an experience they’ve never had. (It is should be obvious, but I am not suggesting that writers cannot write outside themselves.) But the solution comes from those people of color, those women, those gays and lesbians, those transgendered individuals who bring their own unique experiences to their fiction. I don’t think it’s absurb to say that they we tend to write best what we know best. Sure, we might not know what it’s like to shoot an Arab man for no comprehensible reason or to kill a pawnbroker because we want to tap into our own little Napoleon, but we do know what it feels like to be in our own skin. That no one can take away from us. Women, I would bet, write women best. Same with any other category.

If we want more “strong female characters,” we need more strong female writers. There, fortunately, have been quite a few so far: for example, George Eliot, Jane Austen, Zora Neale Hurston, Virginia Woolf, Toni Morrison, Flannery O’Connor, Alice Walker, Alice Munro, Tillie Olsen. (Literature, for the most part, is one of the most democratizing of the narrative artforms.) But frankly, that’s not enough. It’s easy to say that women aren’t recognized enough in the arts, and to a certain extent, that’s true. But the bigger issue is that greatness doesn’t appear in small numbers. Just look at film. Name all the talented female directors. Julie Taymor, Kathryn Bigelow…and then? And neither of those two would I call great. (Though I would argue Taymor is far more talented visually, unfortunately, her films, like David Fincher’s, are only as good as their scripts.) There’s such a small pool of female talent–of any underrepresented group–that greatness among their ranks is limited, if not shown at all. We need a larger sample size.

We tend to forget that dreck is not unique to any one group, especially, under today’s microscope of social justice. There are a lot of great male writers; however, there are also a lot more bad male writers. Just look at the latest issue of New Letters. All three pieces of short fiction are written by men, and all three suck. All over America, we have these shitty–but somehow successful–artists, whether James Patterson or Michael Bay. So the question remains: Why shouldn’t those spots go to anyone else?

September 6, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

For a while now, this blog has been promoted as a place that talks about academic issues, the nuts and bolts of writing, and the art of games. One of those, of course, has been much neglected. I might make a passing mention of a game here and there, but overall, I haven’t really taken the time to talk about it at length–which is a shame. Now, however, I intend to rectify this oversight with some musings on an approach to games criticism.

#GamerGate has been widely misunderstood as a whole, in much the same way we view any leaderless grassroots movement. It’s pretty hard to talk about something so amporphous and divergent. Some people seem to think it’s about ethics in games journalism. Others say it’s about the caustic influence of identity politics. Others say it’s an excuse for harassment. In many ways, all of these things are valid, I think, but it also demonstrates how much we like hearing ourselves talk. Whatever the movement represents to you is probably predetermined, and there’s likely no way to sway you to another opinion. Sadly, most of these topics are relegated to different spheres. The people who face harassment in and around the industry, of which there are many, shed light on a serious topic, one we should all be committed against. Of course, that doesn’t mean we should ignore ethical breaches or halt discussions about how to assess art. The people who bemoan the invasion of identity politics have legimate claims too, issues we have to consider, but it doesn’t mean they should blithely brush aside the discrimination people face. Instead of actually engaging in these peripheral conversations, most of the time, these true believers continue to preach from their megaphones and silence any dissent.

In truth, there are a lot competing ideas, an argument without focus. Is there sexism in games and the industry? Most likely. Is it annoying to read a review that epouses a philosophy and provides little analysis and cherry-picked evidence without assessing whether a game is “fun” or not? Sure. Are journalists, and this doesn’t even just apply to games journalism, a little too close to their subjects? Absolutely. These things are largely hard to disprove or refute. They just kind of are. However, much like Occupy Wall Street, I don’t think the conversation has been entirely productive. It’s a lot of self-pleasure, appealing solely to one’s own audience: mental masturbation. Frankly, that doesn’t interest me. Instead, I’d rather look at solutions to definitive problems, and since my background is dedicated to the creation and appreciation of art, it only makes sense to talk about games criticism at large.

It’d probably best to start with an admission: Most mainstream criticism, of all art, is garbage. It’s not about careful consideration, thorough analysis, and nuance. In most cases, the critics we find in newspapers and blogs–those who critique our books, our films, our video games–don’t spend a lot of time crafting their argument. They don’t mine every available piece of evidence. They don’t look at a text as whole. They don’t qualify their statements or follow through on the logic of their thinking. As Allan Bloom puts it in The Closing of The American Mind, “[T]here is no text, only interpretation.” In other words, they ignore the very thing under scrunity. They don’t care what it actually says, but instead, they care what they believe it to say. Of course, mainstream critics have deadlines and numbers to meet. It is not, after all, academia, where those things aren’t as important. What I’m trying to say is that contemporary critics react emotionally. They feel their opinions to be true.

And that, to me, is the biggest problem. If we aren’t thorough, if we don’t apply the skill of close reading, how can we really make any kind of aesthetic judgement?

Most games critics don’t seem to have a theoretical basis for their, admittedly, abitrary scores. They say the graphics are great or that the story drew them in. The truth is, I could give a fuck how it made you feel. What I want to know is why. I want evidence. This, again, isn’t entirely their fault. Now, more than ever, people flip shit if there’s even the suggestion of a spoiler, as if the fun of a piece of art is the mystery of what happens next. This, as I’ve said in the past, is a load of bullshit. It doesn’t ruin the experience: It enhances it. When we know what to look for going in, it makes appreciating the craft that much more satisfying. That does not mean that we should expect only to find what the critic has found. If anything, the real disaster would be to allow one reading to bias our own reading, but such a matter is of an individual’s own sense of discovery, their own inability to think for themselves.

So the question arises: How do we assess this artform? What criteria should we use to choose play or not play?

The answer is largely subjective, as we all have different approaches to art, but I think we can, thanks to New Criticism, lay a foundation. Every game is about something, a central tension, an idea, a philosophy its trying to express. Our job is to discover it, which we often do quite quickly. In a mere matter of moments, we can articulate the theme of just about anything. Yet if you were ask us how we had made such a realization, we would presumably say it just is. This, to me, is the first mistake. We need to actually show that theme and how it’s communicated, which means a thorough, careful reading based on a preponderance of evidence. Just as a math teacher asks us to show our work, so must we. The theme should inform every facet of the text: Its setting, its graphics, its design, its gameplay, its characters, its structure. If we talk explicitly, specifically about these elements, then we can form an argument and make our case.

To an extent, there are already a few publications who take this approach, like IGN or The Completionist. However, most reviewers who take such an approach fail to deliever compelling and in-depth evidence to their claims. Again, the text just simply is.

There are others out there, Polygon and Kotaku in particular, who have started to inject moral studies into their reviews. (Polygon’s review of Bayonetta 2 comes to mind.) As an academic, this isn’t all that egregious to me. Feminist, post-colonial, queer, and Marxist criticisms are not exactly new. However, I can understand the anger consumers feel coming into a review expecting to learn whether it’s fun or not and then hearing someone talk about gender roles and objectification. “What does it have to do with the game?” they ask. Most gamers aren’t aware of the jargon of cloistered academics. That’s not to say we shouldn’t practice these approaches or that they can’t serve as a guide for our criticism (it is very easy to marry that framework with New Criticism), but more so that we, as consumers, should know what we’re getting into.

So let’s get to the point here: Games publications should announce their critical lens. I want to know where you’re coming from. How are you looking at a game? What are your criteria? What do you privilege in your assessment? Most editors give some lip-service to these ideas, but none really ever declare a manifesto, a reason for their existence. Presumably, they assume we should learn this by reading the magazine. It’s a nice thought, but I think it’s a bit unreasonable. There’s so much to learn out there, so many opinions. Can I really read through every article you’ve published to get a feel for your publication just to decide if it’s for me? And what if the editor changes and hence their vision? That’s a lot to expect from anyone.

In short, there are two problems with games criticism as I see it. One, when dealing with a specific text, reviewers/critics fail to give specific examples to illustrate their claims and/or investigate their own criteria for what makes a game worth playing, which is why consumers resent the injection of moral studies in what they believe to be an objective analysis. Two, games publications don’t really announce their editorial vision. Though I don’t think these solutions will ever take a hold any time soon, I still hope that at least one publication comes along who adopts such practices. Maybe if such things were commonplace, we’d see a little less anger in the comments and a little more rational, intelligent debate.

August 10, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

Lately, I have heard a lot about ideas such as cultural appropriation and cultural exchange, ideas of privilege and oppression, ideas, which, ultimately create a quandary for the artist. Of particular note, has been the increased calls for diversity, both behind the art and in the thing itself. These goals, I believe, are admirable and well within reason. It is largely benign, of neither insult nor disfigurement to American art at large; instead, it is to our shared benefit. We should have a plethora of unique and boisterous voices to admire. Good art is always worth striving for. However, there seems to be strain of these criticisms that seems ill-defined at best, an uncertainty, an inability to articulate exactly what the critic wants. The closest I have to a definitive statement comes from J. A. Micheline’s “Creating Responsibly: Comics Has A Race Problem,” where the author states: “Creating responsibly means looking at how your work may impact people with less structural power than you, looking at whether it reifies larger societal problems in its narrative contents or just by existing at all.” There are a couple of ideas here that I take issue with, ones that don’t necessarily mesh with my ideals of the artist.

Hegel wrote that “art is the sensuous presentation of ideas.” Nowhere is the suggestion that art comes attached with responsibilities. I’m not saying that art doesn’t have the power to shape ideas, but more so, there is often a carefully considered and carefully crafted idea at the heart of every work of art. That overarching theme is given precedence and whatever other points a critic discerns in a work fails to recognize the text’s core. In other words, how can we present evidence of irresponsibility of ideas that are not in play?

This, no doubt, branches out of the structuralist and post-structuralist concepts of binary opposition, and most of all, deconstruction’s emphasis on hierarchical binaries. I no doubt concede that such things exist in every text: love/hate, black/white, masculine/feminine, et cetera. However, the great flaw in this reasoning is that these binaries, even when they arise unconsciously, conclusively state a preference in the whole. Such thinking is a mistake. If we reason that such binary hierarchies exist, why should we conclude that they are unchanging and fixed? Such an idea is impossible, regardless how much or how little the artist invests in their creation. Let’s take a look at a sentence–a tweet, in fact from Roxane Gay–in order to make such generalities concrete:

I’m personally going to start wearing a lion costume when I leave my house so if I get shot, people will care.

We will ignore the I of this statement as it is unnecessary in order to make this point. We have to unpack the binaries at play. First, we note the distinctions in life/death, animals/humans (and also humans/animals). These binaries exist solely inside this shell, yet, if we consider this as a part of a much larger endeavor, we are likely to find contradictory binaries in other sentences. When exactly can we decide the author has concluded? How can we determine the author’s point? Can we ever decide? Now think of applying such an act to a text of 60,000, 80,000, 100,000 words. There’s no doubt it is possible. Yet, should we sit there and count any and every binary that privileges one of the terms? Would that move us any closer to a coherent and definitive message? I find it unlikely.

Of course, I’m not advocating for a return to the principles of New Criticism nor I am saying that post-modern philosophy and gender/race/queer theory have no place in the literary discourse, but to simplify a text, to ignore its argument, seems inherently dishonest. Critics are searching for validation of their own biases, a want to see what they see in society whether real or imagined. This is by no means new, as Phyllis Rackin notes in her book Shakespeare and Women, “One of the most influential modern readings of As You Like It, for instance, Louis Adrian Montrose’s 1981 article, ‘The Place of a Brother,’ proposed to reverse the then prevailing view of the play by arguing that ‘what happens to Orlando at home is not Shakespeare’ contrivance to get him into the forest; what happens to Orlando in the forest is Shakespeare’s contrivance to remedy what has happened to him at home’ (Montrose 1981: 29). Just as Oliver has displaced Orlando…Montrose’s reading displaces Rosalind from her place as the play’s protagonist….” Rackin’s point is clear: If you go searching for your pet issue, you’re bound to find it.

#

I am not fond of polemical statements nor do I want to approach this topic in a slippery-slope fashion as it simplifies a large and complex issue which is too often simplified to fit the writer’s implicit biases. In order to explore thorny or shifting targets such as these, we need to strip away whatever artifice clouds our judgement and consider the assumptions present therein. Unfortunately, most of the discourse has been narrowly focused, boiling down to little more than a sustained shouting contest, a question of who can claim the high ground, who can label the other a racist first. This is not conducive to any dialogue and only serves to make one dig in their trenches more deeply. It is distressing to say the least.

One of the assumptions most critics make goes to the pervasiveness of power, that power is, as Foucault puts it, everywhere, that there is no one institution responsible for oppression, no one figure to point to, but instead, it is diffused and inherent in society. Of course, Foucault’s definition of power is far from definitive and impossible to pin-down. Are we merely subject to the dominance of some cultural hegemony, some ethereal control that dictates without center as some suggest? This, it seems to me, only delegitimizes the individual. Foucault suggests that the subject is an after-effect of power; however, power is not a wave that merely washes over us. It is a constant struggle for supremacy. Imagine it on the smallest scale possible: the interaction of two. Even when one achieves mastery over the other, the subordinate does not relinquish his identity. These two figures will always be two, independent to some degree. The subordinate is relinquishing control not by coercion but by choice. Should the subordinate resist, and he does so simply through being, the balance of power shifts however slightly.

Existence is not a matter of “cogito ergo sum,” but a matter of opposition, that as long as there is an other, we exist.

#

Many people have made the distinction between cultural exchange and cultural appropriation, that the former is a matter of fair and free trade across cultures while the latter is an imposition, a theft of cultural symbols used without respect. While this sounds reasonable, the exchange is impossible.

There is no possibility of fair and equal trade: One will always have power over another.

We assume that American culture is some definable entity, that there is some overall unity to it, but just as deconstructionists demonstrated the unstable undecidability of a text, a culture too is largely undecidable. A culture is not some homogenous mass, but a series of oppositions at play, vying for influence.

We can use myself as an example. Of the categories to which I subscribe or am I assigned, I am a male, cis, white, American, Italian-American, liberal, a writer, an academic, a thinker, a lover of rock n roll, and so on. Each of these cultures are in opposition to something else: male/female, cis/trans, white/black, white/asian, white/hispanic, et cetera. These individual categories form communities based on shared commonalities, but to suggest that these segregating categories can form a cultural default or mainstream is deceptive. Each sphere is distinct from the other, a vast network of connections that ties one individual to a host of others based on one facet. Yet this shared sphere does not create a unified whole. There is no one prevailing paradigm. It is irreducibly complex.

So what’s the point here?

Cultural appropriation, if such a thing exists, is inevitable.

#

It should go without saying, but these ideas of oppression and power are ultimately relative. Depending on what community you venture into and your privilege inside it, you will find yourself in one of these two positions—always. America is as much a text as a novel or any other piece of art. We can count up our spheres of influence, those places we are powerful and those places we are powerless and come no closer to overall meaning.

This is not a call to throw up our hands in nihilistic despair for the artist. The artist would be wise to remember their own power, their ability to draw the world uniquely as they see it. If an artist has an responsibility at all, it is not to worry what part of the binary they are or are not privileging, what hierarchy they summon into being. Someone will always be outraged, oppressed, angered as long as they are looking for something to rage about, regardless of whether it is communicated consciously or not.

Freudian criticism often looks at the things that the author represses in the text, the thoughts and emotions that the author is unwilling to admit explicitly. When asked to give evidence, the critic often claims that the evidence does not need to be demonstrated because it cannot be found: It is somehow hidden. And it is this vein, that sadly, has infected our current approach to texts. We co-opt a text for our own biases, to express what the critic can project onto them, rather than what the work itself describes. We look for any example which might fit our goal and consider it representative of the whole. That is cherry-picking at its most obvious, and an error we should all strive to avoid.

We tend to forget that there are bad texts available to us, that do absolutely advocate the type of propaganda that critics infer in works that approach their subjects with care and grace. How can we scrutinize The Sun Also Rises as antisemitic, as heterosexist, as misogynist when we have books like The Turner Diaries that clearly are? How can we damn Shakespeare for living in a certain era? How can we cast out great works which recognize the complexity of existence and ignore those which undoubtedly make us uneasy?

To the point, we are more enamored by the implicit over the explicit. The central argument of a text is what deserves our attention, how it is made and whether it is successful. We cannot presume to know the tension of other binaries as that text is still being written, constantly shifting, unending in its fluidity.

#

It is easy to make demands on the artist. Anyone can do it. Criticism is one of the few professions that does not require any previous knowledge or qualification. It is, at its heart, an act of determining meaning, and many, I would argue, have been unsuccessful. The hard part is creating meaning. And to those who make some great claim on what art should or should not do, my advice is simple: Shut up and do it yourself, because, by all means, if it’s that easy, demonstrate it.

July 19, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

I was introduced to Spartan via Twitter. I’m not sure how exactly, but I’m glad I was. The magazine’s aesthetic is clean and sparse, both in prose and in design. It’s clear the editors want to put the stories at the fore, and that’s an approach that is much appreciated, not too mention rarer than ever.

One of the stories I read was “Going, Going” by Anton Rose. It’s a slice-of-life, maybe a little over one-thousand words, and for the most part, it’s flash fiction done well. I know I’ve been critical of the form in the past, but this story reminds me that there are people who recognize the strengths of the form, like Rose. The problem with most flash fiction is that it often serves as a good opening to a much fuller and richer story that’s buried beneath a pile of description and exposition and typically forces profoundity onto the unprofound. Most writers of flash fiction subvert the elements of fiction not out of necessity but out of ignorance as they present their trite moments of reflection. “Going, Going,” however, largely succeeds in proving my bias wrong.

At first, it seems as though it’s one man’s struggle with cancer, but quickly, it devolves (in a good way) into something else entirely, tapping into magic realism and surrealist traditions. The twist is a unique one that surprises as much as it excites.

The structure too is pretty smart. Rather than dwell on one scene for its entirety, Rose chooses to use a series of snapshots to depict the enormity of his nameless protagonist’s situation, and though there’s no real sense of cause and effect as they bleed one scene to another, there’s still an overall sense of progression.

Rose’s primary conceit, the loss of hair and appendages, serves as the ticking bomb of the story, creating a sense of dread in the reader as the protagonist nears closer and closer to nothingness.

The prose has a Kafkaesque flair to it, not necessarily in the length of sentences or the complexity of their construction, but the flatness with which the narration presents the character’s situation.

He was sitting on the toilet one afternoon when he felt an itch at the tips of his toes. He pulled his feet out of his socks and shoes so he could scratch them, but his toes weren’t there anymore. He checked his socks, but they were empty.

There’s an uncanny aura to everything, as the reader is denied access to the protagonist’s thoughts and feelings. We are left to our own devices and wonder if the character is disturbed by his metamorphosis as much as we are.

The nameless protagonist seems purposeful too. I think Rose wanted him to be a everyman-type character, one whose situation is relatable to anyone, a physical manifestation of the human condition. Rarely, does the protagonist react with horror or shock but, instead, with bemused indifference, recognizing the inevitablity of his fate, even as he watches others around him disappear:

A couple of days later he was sitting in the clinic again. The guy who normally sat to his right wasn’t there. Hadn’t been there for a while, now he thought about it. He tried to remember the man’s name, but he couldn’t bring it to mind. He only saw the chair, empty.

It’s a beautiful piece, even if a bit depressing, executed with a subtle grace. And even though it’s short, it still abides the governing laws of story. It has the structural elements we expect from fiction and succeeds in using them: It just uses a unique form to express them–which I think is what we should all strive for as writers. Experimentation is important, but it should never come at the cost of the story. They are one and the same, a part of a whole that must be manipulated as a choice, not a mistake.

Unfortunately, this story isn’t perfect, but few rarely are. The last scene feels like a missed oppurtunity, where the protagonist strips in the park and “melts” in the sunlight. I’m not sure what to make of it. There’s a sense of acceptance in the description, but we never had any real resistance earlier, making the character’s transformation seem dishonest and not earned. Furthermore, I think that last scene probably should have been the story’s fullest, rather than its most slight, and I’d probably attribute that to the story’s lack of interior. The narration is so distant throughout, and this is a place where that change would be justified and appropriate. It would enhance the overall thematic argument. I’m not saying that I don’t like the subtlety of the story–in fact, it’s one of its strengths–but sometimes that subtlety makes things more opaque than clear.

So other than those two minor flaws, this is a very good short story and well worth your time. And most importantly, it reminds us that there are writers who still partake in the tradition, even as they actively revolt against it.

July 8, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

Truth be told, I’m not very familiar with the work of either Matthew Doffus or The Buffalo Almanack. The most I could find about the former was a poem he had published in Barrelhouse, and as for the latter, the most I can say is that I submitted to them once in the past. But that’s about all I know, and frankly, I prefer to keep it that way–at least, for now. I can’t even tell you how much the magazine awards the winner of their Inkslinger contest. But I’m trying to stay purposely ignorant, with as few biases as possible, and bring you an honest critique of the story.

“Shadowboxing” follows the life, career, and death of artist Sara Frye as seen through the eyes of her sister Anita. The story deals with themes of mental illness, youth, and artistic integrity. The most obvious and abundant strength of the story is the prose. For example, when the older sister Anita, visits Sara after her first suicide attempt, Doffus writes:

Back at the hospital, she flapped her bandaged arms at me and called me Auntie, as though nothing unusual had transpired. Dark circles ringed her eyes like bruises, and her normally pale skin looked translucent. She’d lost weight: her collarbones and sternum stood out beneath her gown. Her blond hair, shoulder-length when she’d colored it with markers years earlier, had been hacked into a lopsided bowl cut that called attention to her pointy ears.

The prose has a clarity and beauty that is rare even among literary writers. Although a simple description, Doffus seeks out le mot juste and paints a striking image in the fewest words possible. Furthermore, the sentences, aside from being lean and muscular, don’t necessarily draw attention to themselves. He’s not attempting to push his sentences to the breaking point or trying to be as elliptical as possible. Neither choice seems particularly important to the author, not that I think that those moves would improve the story. As I said, his prose is simple–but recognize that it isn’t simplistic. Just because most sentences are variations of the typical noun-verb construction does not limit the writing. It still has a clear and distinct rhythm and never once does it feel like a chore to move from sentence to sentence. Doffus adds enough variety with introductory prepositional phrases, complex, compound, compound-complex sentences, and appositives that his prose has a momentum that beckons the reader to read on. His descriptions are probably the best part of the story.

Surprisingly, the peripheral characters are well-developed too. Lines like, when Sara marries a fellow artist and brings him home to the family, “For the rest of [Anita and Sara’s parents] lives, they couldn’t understand Ravi’s stuffy, conservative suits were an artist’s affectation, not a sign that he was a member of the Nation of Islam” tell us a lot about the the parents without wasting the reader’s time. And though Sara seems little more than a manic-pixie dream girl taken to her logical end (which I will get to later), Anita, our narrator, is particularly interesting, as the first thing we learn about her after her sister’s death is that Ravi tells her not to make the suicide about Anita. However, this idea never seems to be followed up. In fact, this missed opportunity leads to the story’s overall problem: the structure and story itself.

The tale begins as Anita tells us that she had learned of her sister’s death via the internet. She says, “Like much of what was written about her, the post made up for a lack of facts with innuendo and attitude.” Yet, this idea never seems capitalized on either. There’s no real contrast of the woman the rest of the world sees and the one her sister sees, at least not in a meaningful way. Most of the story looks at things through Anita’s eyes, her private encounters with her sister. While we do have hints and reports of what the rest of the world thinks, like the French critic who labels her elfe terrible or the journalists asking questions about her at the end or the many awards and honors that Sara has been bestowed, there is an obvious missed opportunity here. If, from the outset, we’re promised a juxtaposition of who Sara was and who people thought she was in the Charles Foster Kane-mold, why is it we’re so often sidetracked? It seems like this part of Sara’s character isn’t fully realized, as though the writer didn’t know the answers himself. Yes, people think she’s brilliant and genius, but what else? That outside portrait of Sara is sorely lacking here. And Anita’s experience shows her as mostly irrational and crazy, but that, at least, has some depth to it because it is shown in scene.

Later on in the story, there’s a dispute between Ravi and Sara, an argument over a painting which he stole from her and passes off his own. This feels more like a distraction than anything else, a plot point arbitrarily thrown into the mix rather than thoughtfully considered. It might be possible to say that the theme of perception could be paralleled with Sara’s public/private image and Ravi’s theft, but again, the writer doesn’t really emphasize this. It feels as though the story doesn’t know what it wants to be. Is it a about who we are and who others think we are or is it about jealously in the artistic world (Sara’s second and successful suicide attempt comes after her estranged husband wins a MacArthur Grant)? Both of these ideas could have served as stories of their own, but here it only causes cognitive dissonance. Even Doffus’s choice of scenes and character interaction, while strikingly realistic, feel wedged into the story instead of arising naturally from a causal series of events. The first scene we get is of Sara as a child, when she gets a Polaroid camera. We get some nice summary, essentially a series of snapshots, that flesh out the character and show her eccentricities, but when the scene starts the conversation is banal and directionless.

Sara tells her sister about why she hangs her Polaroids with nails, “Thumb tacks won’t work…so I use nails.”

Anita replies, “How does Mother feel about this?”

“She made me promise not to hit my thumb…. Like I’d do that on purpose. That’s why they call them accidents.”

These first lines of dialogue should be of extreme importance, but instead, they only add to our confusion. If we fold them into the theme and overall plot, we have to ask, “Are we to question Sara’s death?” Was it an accident? Putting a gun in your mouth seems like a strange accident. Is it to show how Sara has changed by the story’s end? But I would argue Sara doesn’t undergo any change. She has superficial ones but not ones that matter. She’s a manic-pixie dream girl through and through from start to finish. There really isn’t any character here who makes a change, not even Anita. This is what I think does the story in. The prose is wonderful and the characters are interesting and their conversations and thoughts feel meaningful but that meaning is lost on the reader, presumably because the writer was just as unsure himself.

In short, though there are some nice things here and everything here feels cohesive and unified, it ultimately falls apart under careful scrutiny. It’s worth your time if you want a quick and enjoyable read, but overall, it’s a story that’s not worth the analysis because you’ll end up getting frustrated by the ill-defined themes and one-dimensional nature of the protagonist.

May 13, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

I went to see Age of Ultron the weekend of its release. And even though I was less than excited to see it (more obligated than anything else), I ended up coming out pretty happy about the eleven dollars I had spent. It wasn’t the best film ever but neither was the first Avengers. In fact, I like the second one slightly more. But in my two-and-a-half hours of viewing, and the subsequent hour or two of thought I gave it, did I ever once feel as though the film presented any philosophical message that I found particularly uncouth. In fact, I took part in a podcast that same day, and it wasn’t even an issue that we broched.

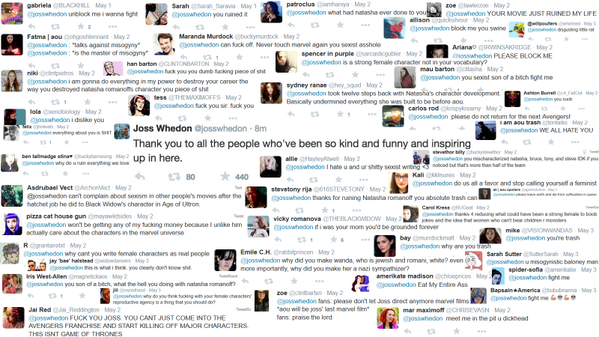

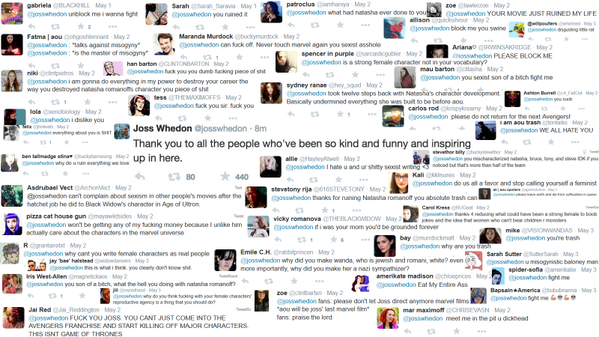

But then along came twitter.

Now whether Whedon left twitter because of these tweets or not isn’t my concern. I’m more so bothered by the pure bile that these people are spewing at an artist whose trying to make something beautiful. And frankly, this is coming from someone who never saw all the fuss over Joss Whedon in the first place. (Yes, I think he has talent: I just don’t think he’s the end all and be all when it comes to witty dialogue.) But why are people so angry? And more importantly, are they right?

Many a spoiler ahead….

One criticism I read came from blastr.com. Two of their critics were discussing Age of Ultron and bemoaned the “forced” relationship between The Hulk and Black Widow. Krystal Clark made the following remark:

“And I’m gonna go there and take a lot of issue with the fact that, in order to make a point for Banner about what being a monster is, they chose to get the one d**n developed female superhero we get in the MCU’s ovaries involved. It’s terrible how Natasha was tinkered with, and a huge decision was taken out of her hands, but wouldn’t it be a lot bolder and more progressive to bypass an antiquated gender bomb like fertility (which, come on, do we even want to touch on that in a superhero tentpole movie?), and just feature a strong, decisive woman like Natasha choosing a super-spy/Avenger life? Because women are so often the girlfriend, wife, mother in every movie out there, you can’t throw in something like a woman not being able to conceive and not have some process it as another thing that Natasha can’t do, instead of focusing on everything she can do.”

This seems to be a problematic analysis of their relationship and the farmhouse scene in general. First, Clark seems to be saying that in order for Banner and Romanov to be able to relate, monster-to-monster, they had to discuss their monstrous details. And according to Clark–and many others–being infurtile is on pare with being a giant green rage monster.

This, I believe, is not the case.

The monstrous side of Black Widow comes not from her inability to have children but from her sins as an assassin, which is shown vaguely in her vision brought on by Scarlet Witch. In order to be a weapon, Black Widow had to be a bad person, had to betray the innocent–much like the Hulk. And that’s the connection, I think, the two make. But when Banner says he can’t have what Hawkeye has (a farmhouse and a wife and three children), Romanov tries to comfort him by saying that she can’t have it either. That’s why it makes sense to jump into a relationship.

Furthermore, Clark asks why does the film have to have this relationship when it could be just Black Widow kicking ass. Now, I know this might sound crazy, but if you spend anytime watching shows or films with bad ass chicks in them, there is often something wrong with that bad ass chick. Just look at a character like Olivia Benson from Law and Order: SVU.

Benson, for a good portion of the series, didn’t get involved in serious relationships. She was a fuck them and leave them kind of woman. Why? Because a woman is tough, she also doesn’t have the ability to love. Of course not, just look at a character like Kima Greggs from The Wire. But that show, unfortunately, is an exception to the rule.

I can think of very few films where a character isn’t involved in a relationship in some way. Look at a movie like Die Hard. John McClane isn’t just a New York cop fighting terrorists: He’s fighting terrorists to save his wife and fix his marriage. But he’s still a bad ass, just a vulnerable bad ass.

How about John Wick? He is defined by his husbandry, devoted to his wife even in death.

All characters worth watching love someone, and Black Widow’s love of the Hulk makes sense. She loves him because he’s not a fighter. It’s something that comes easy to her and everyone around her. She wants someone who’s different. And just because she gave up her ability to have children biologically doesn’t mean she’s a bad woman or a monster. It means she has different priorities. It means she’s happy to be Aunt Nat, not a mother.

And as for Clark’s suggestion that this film turns her in the “girlfriend, wife, mother,” it really doesn’t hold much weight as she seems to get more screen time than Banner. In fact, people are quick to say that she’s become the stereotypical damsel in distress. I guess they missed the twenty minute action sequence where she single-handedly turned the tide of the war against Ultron. I guess they were just supposed to get the Vision back without any trials or tribulations. I guess movies and stories should just be consequence-less.

And of course, who comes to rescue her? Not the Avengers, not even the Hulk, but plain old Bruce Banner. That, I think, says something. It shows growth in his character and hers. He, for once, isn’t the pansy wuss scientist without turning green, and she, for maybe the only time in the series, is vulnerable, needing some help. It doesn’t invalidate her existence. It doesn’t make her weak. It just means she failed–but only for a moment. Once she gets out of her cell, she’s back to ass-kicking. And not only that: She’s saving lives too.

That’s a pretty stark contrast to the woman we see earlier in the film.

Widow goes from someone who takes lives and must carry those sins with her to someone who saves them. That’s why she’s able to go back to the Avengers and work with Captain America to assemble their new squad. She has found meaning in what she’s doing. Sure, she still wants a life with Banner, but it doesn’t define her. This isn’t Bridget Jones’s Diary or Twilight. She’s not that woman who is successful in all avenues except love and feels horrible about it. Those kinds of characters are the worst propaganda as their lives are meaningless without a man. But in Black Widow’s case, it’s icing on the cake. By the movie’s end, she has found some real happiness, even if it is bittersweet.

But of course, if you only spend time analyzing one scene and cherry pick your evidence, I guess it’s easy to complain that a movie is sexist.