October 1, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

A recent post here has garnered some attention from the internet, in particular, poet Joey De Jesus. He sent me a few messages on Twitter, reposted my article, and surprisingly, the two of us had a spirited–but in the end–friendly debate. We still disagree vehemently, but it might have been actually productive, which is odd because it took place on the internet. I would like to thank Joey for tweeting the article and posting it on Facebook, since after all, my goal is to get people talking about criticism, even if some of the conversation has reduced my argument to “white tears,” which, to my knowledge of the phrase, is an incorrect application. I don’t think it’s necessary to take others to task by name for their simplified engagement, as such arguments don’t actually state ideas or even offer criticism but instead, rely on the use of rhetorical devil-terms, designed to shut down argument rather than encourage it. With that said, however, I do want to get at the heart of what I began with “Kenneth Goldsmith and the Writ of Habeas Corpus”: Modern mainstream criticism has lost its way. Therefore, to Joey, because I hope you’re reading this, thanks.

So let me begin by saying I think I might take for granted the education I had as an undergrad. Many of today’s critics, who, as I’ve said before, are pretty highly educated, went to far more prestigous schools than me. But the thing I failed to recognize is that maybe those educations aren’t necessarily on the same page as mine. I don’t know to what extent many of today’s writers and poets learn about literary theory and the philosophical underpinnings behind a broad spectrum of critical approaches. It really depends on the program, and mine was very theory-based. (This is not to imply that your program was bad, dear reader, nor am I trying to talk down to those of you who bristle at the thought of theory. Presumably, we, and our respective programs, value and promote different ideas.) Furthermore, I’m well aware of the suspicious attitudes writers have voiced in the past about literary theory, as if it were some kind of slight of hand meant to distract, as if it undermines their authority as authors. (It does, and it should.) But for me, my undergrad experience has made my discovery and investigations of texts far more enriching, far more worthwhile–not to mention enhanced the thought I put into my own fiction. One text could, through the power of criticism, be seen through a multitude of lenses. We can see The Great Gatsby as a New Critic, a Freudian, a Feminist, a Structuralist, a New Historian, a Post-Colonialist, and one of my particular favorites, a Deconstructionist. However, I never felt comfortable identifying as any one type of critic. There were, after all, enormous benefits to each approach–as well as drawbacks. None, as I saw it, were perfect. Often, I would use the approach that I thought best fit that text. But my question is why these critical discourses are just that: discourses and not a discourse. Why can I not take these varying ideas and make them work together, rather than compete for authority?

And that’s exactly what I plan to do now.

The basis for any modern critical discipline has come from many of the tenets of New Criticism, in particular, the intentional fallacy and close reading. Just about every other critical approach relies on these two ideas. One, as stated in “The Intentional Fallacy” by Wimssatt and Monroe and later essentially expanded upon by Barthes as “the death of the author,” the author does not determine meaning. He or she has no greater claim on a text than anyone else. The author does not assign his or her own meaning and value. Two, the practice of close reading is meant to scrutinize each word, each mark of punctuation, every line break, every enjambment, every metaphor and simile, in order to determine how those choices determine the text’s meaning.

However, New Criticism does have its flaws.

It aims to discover the best interpretation. This, I would argue, is a mistake not only because it assumes there is one best interpretation but because that best interpretation focuses on what the text is actually about. This is where I start to differ with most critical theorists. I say that a text already has a specific meaning, that it is about that one specific idea (or specific ideas). That theme or meaning is fixed. Everything else about it is a quibble, because the rhetoric is clearly aimed at that goal, if it is a good, well-constructed text. We must recognize that at first. The other problem with New Criticism is its emphasis on “the text itself.” It dismisses valuable concepts in the rhetorical traingle like context, author, and audience for intent. Many of these points of the triangle have, thankfully, been reinstated and emphasized through the many different schools.

But, as I’ve said before, each new school of criticism only seems to acknowledge just one part of the triangle–except for Deconstruction which, at its worst, throws up its arms in an act of literary nihilism and says that meaning is “undecidable.” What would it look like if it acknowledged all parts of the rhetorical triangle, not just one? What if we married the princples of literary analysis and rhetorical analysis?

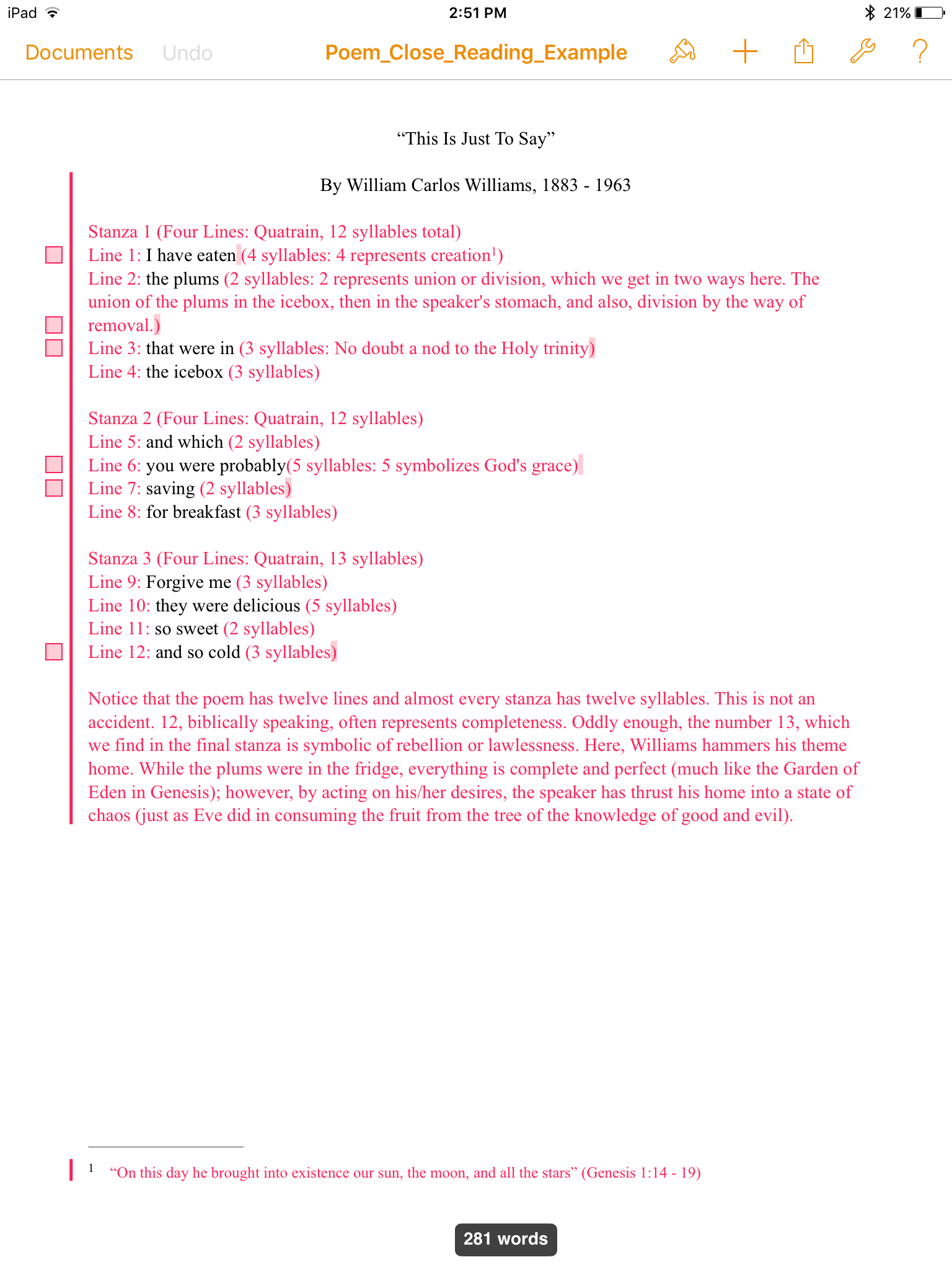

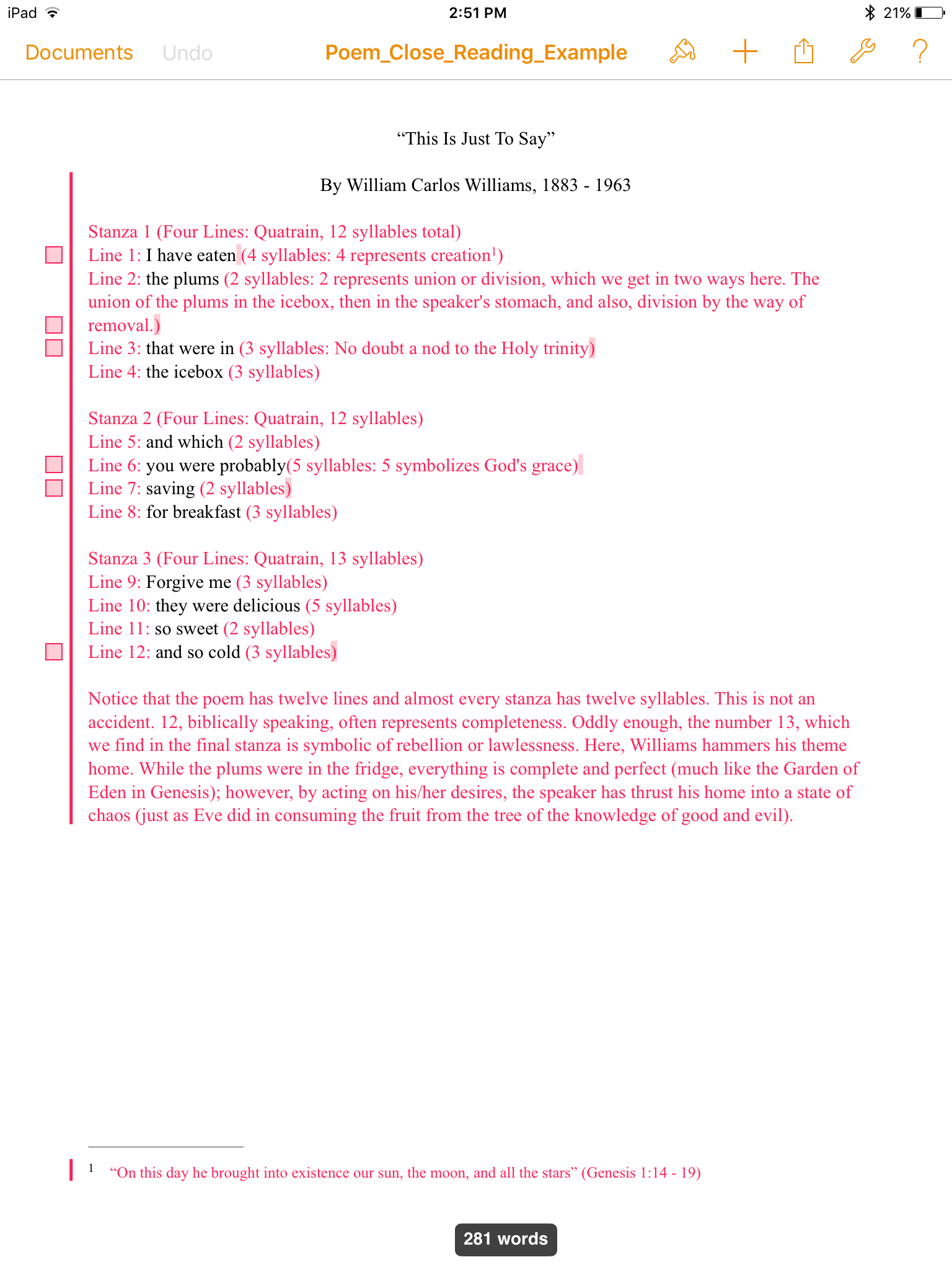

Let’s say we have a text, maybe “This is Just to Say” by William Carlos Williams. The first step should be to do an actual close reading, like this:

Post-It Note 1 (Line 1): This first line tells us a lot. First, we know that this is past tense, since it is “have eaten.” Second, this line is enjambed (it ends without punctuation in the middle of a sentence.). This suggests hesitation on the part of the speaker—the “I” of the poem. There is a clear sense of conflict in the speaker.

Post-It Note 2 (Line 2): Again, we have another enjambed line, putting special emphasis on the fruit itself. This choice seems very deliberate. The eating of forbidden fruit is a popular theme throughout Western literature (think Adam and Eve), and the speaker may be drawing that parallel.

Post-It Note 3 (Line 3): Line three, pauses again to emphasize the fruit’s non-existence and makes us consider its prior location as well.

Post-It Note 4 (Line 6): Here, the speaker introduces the second person, the “God” of the poem, who will, hopefully, forgive him/her.

Post-It Note 5 (Line 7): Notice that the line dwells on “saving,” which follows the line that introduces the “God” of the poem. Our speaker wants to be saved.

Post-It Note 6 (Line 12): This line which ends the poem may be a reference to the medieval view of hell. It was not a place of fire and brimstone, but a cold, cold home for sinners. The thinking was that the further away from God a person was, the further he/she was from God’s light.

This close reading observes the text itself and aims to decipher its “obvious” meaning. And since this is already a pretty simple poem, we know the theme is temptation. It is the tension between yielding and aversion. The privileged term here, seen through the speaker’s indulgence, is yielding, giving in. This, the poem tells us, is the better action. Of course, it is not that simple, since as we learn at the end that the act is both “sweet” and “cold,” signifying that has brought the speaker pleasure because it is delicous and pain because it has caused him or her guilt. The text is, therefore, in conflict with itself.

But in my close reading, I have also made historical and literary connections, which are not self-evident, not explicit. So the question is why? Clearly, I have a bias. I have imbued the text with what I see in it. I am actively constructing it in reader response. So we can say I have been influenced by my cultural landscape, particularly the hegemony of Christianity, as I draw connections between what I observe and with what I associate with what I observe.

And Williams has a bias too. His consciousness has also been shaped by the same cultural hegemony, corrupted by the institutional power of the Church, for the confessional nature of the poem highlights his own anixety over partaking in such a “sin.” Foucault, in his History of Sexuality, claims, “[O}ne does not confess without the presence or virtual presence of a partner who is not simply the interlocutor but the authority who requires confession.” The poem’s speaker’s pleasure may be blissful in the moment, but afterward, it leaves him or her empty and guilt-ridden, for which the only solution is confession. Such an attuitude concerning pleasure is contrary to the speaker’s (and by extention, Williams’s) own biological impulses, trapped in a Pavlovian cycle of pleasure always followed by pain.

Lastly, we must examine the context, the time and place in which the text was composed. Published in 1934, the poem is a product of its era, when, for the decade prior, there was the unbridled hedonism of Prohibition lurking beneath the surface of “dry” America, as all kinds of sexuality was celebrated by those who engaged in the counter-culture, but with the repeal of the 18th Amendment, returned puritanical denial and self-flagellation.

This approach, even as rushed, sloppy, and simplified as it is here, is what we need more of, an observation of all the points of the triangle, one that presents a more complete, complex, and thorough portrait of meaning, which hopefully gets even more complicated when we factor in things like race, gender, class, et cetera. Some may claim this is tedious–and I think it is–but it is also necessary. Criticism is designed to be just that.

Furthermore–and this should go without saying–this approach does not stake a claim on ultimate meaning. It is grounded in Cartesian uncertainity: It recognizes the subjectivity of experience. If anything, it is a Kierkegaardian leap of faith. But the important idea is that it demonstrates how the critic got to where they are. This idea is still very much in its infancy: There is more to be developed here, more to be scrutinized, more to be theorized, more to be tested, more to be investigated, more to be written and revised. But at least, it’s a start.

September 29, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

I know I’m late to this party, but The New Yorker just ran a profile on Kenneth Goldsmith, which many have stayed silent on–and when they have been willing to talk, it’s been outright hostile. The National Book Critics Circle Board retweeted one person’s plea to the editor of Poetry Magazine to retweet the article, which was followed by responses like, “So the lesson here is be a lazy racist and get a lot of press?” and “trash.” One response I found particularly disheartening came from Justin Daugherty, founder of Sundog Lit and editor of Cartridge Lit, who wrote in a now deleted tweet, “KG [Kenneth Goldsmith] is a garbage human.” Now maybe Daugherty and others have had a chance to meet Goldsmith in person and found him to be “trash” and “garbage.” It’s well within the realm of possibilty, but I think, more so, Daugherty is referring to Goldsmith’s poem “The Body of Michael Brown,” which remixes the autopsy report of the young man shot by police whose death served as a catlyst for activism and riots in Ferguson, Missouri. While I think there’s an argument to be made that such an act was “too soon,” social media and the literary blogosphere took a different approach: a shitstorm of moral outrage and indignation. Most arguments against Goldsmith’s performance, from Joey de Jesus’s essay at Apogee to Flavorwire, focused on the act itself, rather than the actual text. And you’re probably wondering: Where can I read/see this? The short answer, ironically during banned books week, is you can’t. And just about none of Goldsmith’s critics have had the chance either. So how, exactly, have so many determined so much based on so little? Don’t we need a text to criticize, to scruntize, to determine whether it was racist or not, as so many have claimed? Shouldn’t analysis and interpretation be based on textual evidence? Probably what I find most distressing is that these writers and editors, who have uniformly condemned Goldsmith and his poem, should know better. They are, first and foremost, artists, and we have all seen plenty of challenges to our freedom in the past and present. But also these are men and women with MFAs and PhDs from the best schools in the country, where the faculty are active scholars who have faced the rigors of peer review, who, presumably, expect the same focused, logical, detailed, thorough analyses from their students. So how, then, have things gone so wrong?

#

In rhetoric and composition studies, we often talk about the rhetorical triangle, which is the connection between the writer, the audience, and the message. This, of course, is framed within a certain context. Most schools of literary criticism place greater value on one of these facets. The New Critic emphasizes intent. The Reader Response Critic focuses on audience. The Freudian psychoanalyzes the author. The New Historian privileges the context. None of these, I would say, are any more useful than the other. In fact, this is one criticism’s biggest flaws–especially as of late. These things, individually, don’t bring us any closer to meaning. They need to be recognized in concert with one another.

Unfortunately, things have only gotten worse.

Due to the increasing influence of identity politics, both the author and the context are all that matter. The text, it seems, has become irrelevant. We don’t care what was actually on the page. That should worry any serious artist or critic. As T. S. Eliot once wrote, “[A] critic must have a very highly developed sense of fact.” But this current trend ignores or disregards evidence which may be contrary to the critic’s conclusions, which often means the diction choices, the form, the imagery, the structure–all of it has been reduced to some irrelevant detail. Critics claim that a text is a vehicle through which our gender roles, class system, and structural inequalities are reinforced rather than challenged. When–and why the hell did this happen? To that, I don’t really have an answer, but I can say that such a trend should be unnerving to any artist, regardless of his or her politics.

First of all, what artist is a complete shill for society? I couldn’t give a fuck about how good or bad he or she may be: Artists are free-thinkers. We’re independent. We have empathy, logic, humanity. We recognize the beauty and benefits of all things–even those we hate. That’s our job. Otherwise, we’re not looking at a poem or a story or a painting, but a didactic piece of shit that our audience will find more alienating than enlightening. Isn’t it OK to be OK with some of the ways that society operates? (This is not a tacit endorsement of racism or sexism or anything of the like, but more so a way to say I don’t entirely mind free markets as long as they’re regulated pretty heavily.) Secondly, I’m not fond of the deterministic philosophy which underpins much of this approach. Whether it’s Tropes vs. Women or an article in the LA Review of Books, the assumption is that society is racist, sexist, and heterosexist, even when it’s actively fighting against it. They preach to us that it is inescapable, but they, of course, have the power to point it out. They are the Ones. They can see the Matrix that you and I can’t. Only they can see, as bell hooks puts it, “the white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.” And while I respect hooks as a rhetorican, I find her conclusion suspect. Let me say, there are absolutely inequalities that exist, problems that exist, but the suggested cause is far too simplistic, as, much like today’s literary criticism, it ignores a lot of contradictory evidence in favor of the ancedotal. Worse still, the solutions are far, far too vague (reform? revolution? change behaviors? change literature?). These issues will not be solved by preachy art: They are solved at the ballot box. (If you became a critic to “make a difference,” try running for office instead.) Art isn’t overly concerned with the right now: It uses the specific to tell us something about the universal.

#

So where do we go from here? I think we need to return to the “scientific” approach proposed by Ransom all those years ago in “Criticism Inc.“–with some caveats, of course. We have to do a thorough close reading of a text in order to discover the intent, but we also need to stress the other points of the rhetorical triangle as well. The message is important, but so is the ways a text undermines its own theme, the constant battle of binary opposites. We, too, must recognize the biases of the reader and the author and the time and circumstances under which it was produced just as we recognize the importance of “the text itself.”

#

So I’d like to leave you with a lie I tell my literature students every semester. I say: In this class, there are no wrong answers. I know that’s not true, but I say it because I don’t want them to be afraid of analysis, to fear interpretation. However, I realize there are “wrong” answers, invalid answers. You can’t just pull shit out of your ass and say it is: You must demonstrate it through a preponderance of textual evidence. This is the cardinal rule of criticism. Yet as my students’s first paper (on poetry no less) approaches, I let them in on this little distinction between valid and invalid arguments. It would appear that many of Goldsmith’s critics skipped that day of school.

September 17, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

I want to start off this post with a definition–two definitions or really, a distinction. Writers and critics often talk about the responsiblity of the artist, what things we should and should not do and how, and as I’ve said in the past, I’m not too fond of burdening creative people with an intent of social justice. (This is not to say art doesn’t provide moral instruction: It is more so that art presents a multitude of moral possibilities and shouldn’t serve merely as propaganda.) That tends to be a recipe for didacticism rather than enlightenment. However, I do think that art itself is meant to do one thing: It shows the world as it is, as the writer sees it. Now I know that may sound absurd, especially when we take into account the many genres available to us. How does the fantasy or sci-fi writer depict the world as it is, when the story takes place in an entirely different universe? Well, the story, no matter the species or world, should connect to those experiences we all share as human beings. There are flaws in human nature, things we don’t like about ourselves as much as there are many strengths. Neither will ever be exitinguished. Societies, even those that appear utopian, still give into our failings. That’s what makes stories worth reading. But if, instead, we depict the world as we want it to be, as we’d like it to be, we begin to tap into something else: pornography. You see, pornography, to me, is not just something that excites or titillates us, but shows us a world we’d like to inhabit. Have you ever watched a porn? Depending on your own personal fetish, you are the viewer of your own particular fantasy. Do you wish women would fawn all over you and decide to have sex with you in moments of meeting you? Do you wish your man would massage you and spend a lot of time on foreplay? Whatever it is that turns you on is there with a few clicks of the mouse. But the world doesn’t operate under those conditions. Our lives are not fantasy, and if you want to see your perfect world in art, you’re only engaging in masturbation.

#

I can’t remember the name of it, but a few years ago a book came out that depicted a homosexual love story in a very conventional way, in the sense that it was merely about two gay people in love with one another. I do not know whether the novel was very good or not, but that’s besides the point. There were two camps of people who had two very different reactions. First, there were the supporters, who felt that the novel was a good one and found it refreshing that the novel didn’t concern itself the societial struggles of the couple. It was just a love story where the characters happened to be gay. The other side thought the novel avoided the issue, that it should have been a main theme of the book. My problem is with the latter group. Who says that the characters have to face the structural oppression of their culture? Can’t they face other challeges? The story is about their love. The writer’s experience and knowledge is what dictated the focus of the narrative, not his or her political agenda. I’m sure the writer is for equality, and if he or she is gay, they are tapping into their world as it is. Does being gay change the governance of a story? Does it mean that the structure must be completely different? Do the characters have to act a certain way? We seem to want to straddle this line of categories are important/unimportant, that we are unique and also part of a group. But if our characters can’t represent that unique perspective, then doesn’t that make for fiction that is largely the same?

#

One of the best movies to come out in a while is Mad Max: Fury Road. It’s brilliant in its construction and reminded us how exciting (and visual) films can be. It’s also one of the most feminist films I’ve seen. Furiosa could have easily been one of those hard-nosed, masculined female characters, the kind that fuck but can’t connect to people. She, however, is Max’s kindred spirit: She is his equal in almost everyway. There are some things Max is better at, like killing a bunch of guys in the fog, but she’s a better shot and driver. They work together in perfect harmony. They’re both sensitive and caring, even when they know they shouldn’t be. And really, if Max wasn’t a crazy drifter, I would even think that the two of them would have been more than happy to start a physical relationship to add their emotional one. They play off one another and serve each other’s stories, helping one another to find redemption. That’s pretty rare on-screen or off.

Unfortunately, we have a lot of narratives that don’t do this–and it’s not because of institutional sexism as so many critics claim. It’s because they’re poorly written, and somehow we’ve forgotten this. (Art is really, really hard. Writing even an essay is strife with traps. It’s hard enough to convey an idea through argument and evidence. When you add story, it gets that much harder. Most of the time, people don’t know what the fuck they’re trying to say with their art.) To me, lovers in any story must be equals; otherwise, what’s the point of putting them together? Han and Leia in Empire and even Jedi are a terrific example. Once their initial courtship ends, they face challenges together. They aren’t spending their time quibbling about stupid shit. They have a mission, and it’s one they attack as a couple. Sure, they might squabble over how best to do it, but they still end up working together as a team.

One thing I find particularly frustrating, in television mostly, is when the writers wedge problems into the relationship–especially after seasons of will-they-or-won’t they. Why is it that these couples end up bickering in the subplot? Sure, relationships aren’t perfect, but why waste my time with something that shouldn’t be a problem? The goal is achieved. Turn your attention elsewhere. The next goal isn’t making things work: It’s taking on the new challenge or challenger as a team.

#

I read an article just recently that says that “Female characters often aren’t allowed to have their own story arc.” I’m not fond of this particular generalization. I can think of few good stories where this is the case. Every character wants something, and by the end of the story, that character should either succeed or fail. In Die Hard, Holly Gennaro wants to be a successful business woman, and she thinks that means she has to sacrifice her relationship with her husband. They, of course, have to put those martial problems aside in order to stop the terrorists, which they do as a team. In the end, she recognizes that they can be together, and presumably, doesn’t need to distance herself from her husband in order to be a success. In Batman Begins, Rachel is Batman’s conscience–and has her own strategy to achieve their common goal. In Iron Man, Pepper Potts primary goal is to keep Stark Industries running. The love stories aren’t tacted on: They’re integral to the story because a good writer knows they should never put something in that doesn’t serve a purpose. But there are plenty of writers who don’t recognize this, and that’s just what the author of that article is inadvertently complaining about. It’s not a gender issue. It’s quality control.

#

Critics say we need more “strong female characters” in art. First, what the hell is a strong character? When I hear it described, what it sounds like is a complete character, one who is complex and real, but people tend to take this as “women need to be badass.” I object to that as much as I do the term “strong female character” for its inaccuracy.

Just about every movie nowadays that has a squad of soliders needs to have that badass female in it. Those characters tend to be as one-dimensional as the rest of the squad. So really, what’s the point? Characters in the background are just scenery. Ripley is complete; Vasquez is just a diversity credit. It doesn’t matter what those ancillary characters are or do, really. If you want a “strong female character,” they can’t come from the background. I think we should recognize that there’s little benefit to making some tertiary or quaternary character a woman, a person of color, a homosexual. How do you characterize this minor player? How can you get your reader to know who they are in the paragraph or two in which they appear? Do we have a shorthand to solve this? We do. They’re called stereotypes.

#

So what makes a “strong” character strong? The answer should have started to reveal itself by now. A strong character is our focal center: It is the protagonist. No other character can compare to them, except maybe the antagonist or love interest or best friend. You can’t render every character as completely as you would like.

And how do we remedy this situation? Obviously, we need more characters of certain categories, but who should create them? Should we burden the predominate writing population (read as white, cis, heterosexual males) with the solution? It might seem blasphemous, but I say no. Critics quibble with any act an author makes, binding them to a strict biological essentialism. They say a writer’s female or ethnic characters are stereotypes or that they’re writing about an experience they’ve never had. (It is should be obvious, but I am not suggesting that writers cannot write outside themselves.) But the solution comes from those people of color, those women, those gays and lesbians, those transgendered individuals who bring their own unique experiences to their fiction. I don’t think it’s absurb to say that they we tend to write best what we know best. Sure, we might not know what it’s like to shoot an Arab man for no comprehensible reason or to kill a pawnbroker because we want to tap into our own little Napoleon, but we do know what it feels like to be in our own skin. That no one can take away from us. Women, I would bet, write women best. Same with any other category.

If we want more “strong female characters,” we need more strong female writers. There, fortunately, have been quite a few so far: for example, George Eliot, Jane Austen, Zora Neale Hurston, Virginia Woolf, Toni Morrison, Flannery O’Connor, Alice Walker, Alice Munro, Tillie Olsen. (Literature, for the most part, is one of the most democratizing of the narrative artforms.) But frankly, that’s not enough. It’s easy to say that women aren’t recognized enough in the arts, and to a certain extent, that’s true. But the bigger issue is that greatness doesn’t appear in small numbers. Just look at film. Name all the talented female directors. Julie Taymor, Kathryn Bigelow…and then? And neither of those two would I call great. (Though I would argue Taymor is far more talented visually, unfortunately, her films, like David Fincher’s, are only as good as their scripts.) There’s such a small pool of female talent–of any underrepresented group–that greatness among their ranks is limited, if not shown at all. We need a larger sample size.

We tend to forget that dreck is not unique to any one group, especially, under today’s microscope of social justice. There are a lot of great male writers; however, there are also a lot more bad male writers. Just look at the latest issue of New Letters. All three pieces of short fiction are written by men, and all three suck. All over America, we have these shitty–but somehow successful–artists, whether James Patterson or Michael Bay. So the question remains: Why shouldn’t those spots go to anyone else?

August 27, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

It should go without saying, but now, more than ever, we have an near infinite supply of art available to us. From the comfort of our own beds, we can stream a film, play the latest Mario Bros., look at the paintings housed in the Philadelphia Art Museum, and download bestsellers straight to our e-readers. A lot of people claim that all of these different forms of media are “competing” for our attention. The novelist complains about the filmmaker who steals his audience. The filmmaker decries those who defect from the big screen to the TV screen. Even the video game creator bemoans the players who pass over her game to watch someone else enjoy it on YouTube. But this idea is fundamentally backwards. It assumes that all art is on equal footing, that the novelist and the comic book writer and the painter are somehow at odds with each other. It is true that our time is always limited, and we can’t devote ourselves to disparate artforms. However, this doesn’t mean that they compete with each other. They are different experiences with different strengths, different weaknesses. Therefore, why can’t a person play video games on a Thursday, watch a film on Friday, go to a museum on Saturday, read poetry on Sunday, and listen to music all week long? This false dicotomy only muddies the water, clouding the conversation at hand–a side-show distraction that prevents us from talking about what really matters. The real question is why should we engage with art at all.

As I’ve mentioned before, Hegel gives one of the finest definitions of art: It is the “sensous presentation of ideas.” In other words, art appeals to our sensory experiences, not solely to entertain, but to teach us about ourselves, about the lives we inhabit, about how to live. This isn’t to say that art is inherently didactic or preachy. (In fact, I would argue that is a symptom of bad art.) It’s more so a case of bringing our attention to serious questions about life. Camus makes us question modernity, morality, our own existence. Bioshock asks whether we have free will, questions about human and player agency, about Randian philosophy. The Dark Knight demonstrates the tension between choas and order and the moral costs of post-9/11 America. Even Dali, in his surrealist nightmares, asks us to question our own reality, our own self of the world. Art isn’t just about good technique or grabbing our attention or being unique: It’s a messy attempt to answer unanswerable questions.

Since this blog is dedicated to the literary arts, the question arises, “Why study literature?” Think about it for a minute. Really think about it. A video game is far more interactive than a poem. A film is better at showing imagery. Sculpture is more tactile. You can view an entire painting in an instant, but a novel may take you several hours to finish. So why the hell should I read a book? What makes it so great? What does it do better than anything else? What’s missing from the rest of those forms? A book, more than any other medium, allows us to access the mind in ways that films or painting or video games can’t. Just look at some of your favorite literary characters: Gabriel Conroy, Raskilnikov, Anna Karinina, Oscar Wao, Milkman, Oliver Twist, Holden Caufield, Nick Carraway. Now think about how many of those characters succeeded on film. Not many. So what’s missing? Why are those characters so endearing on the page but so lifeless on screen? It should be obvious. Those characters are unique to their medium, designed specifically for it. They work, and we care about them, because we have access to their interior lives just as much as their exterior lives. This isn’t to say that all great literature dives feverishly into a character’s soul, but even those minimialist authors–your Hemingways, your Carvers, your Bankses–still give us some insight into the person behind the person. Poetry, one might argue, does this even better than prose, as it cuts out the story (though it may have one) and jumps straight into the soul. No other medium can express emotion or thought like literature. Other forms may have approximations, but they can never claim that as one of their strengths. Just consider how often people complain about narration in film. (It’s visual media, after all.)

We read to discover that we are not alone in the world, that others exist whose experiences are our experiences, that we are all a little bit crazy. We might not know what it’s like to kill an old pawnbroker or to serve in World War II during the bombing of Dresden or have fallen madly in love with a man who is not our husband, but we know what it’s like to be human, to make mistakes, to want things, to hide things from ourselves, to suffer.

Seneca, the great Roman stotic philosopher, when forced to commit suicide by Emperor Nero, comforted his family, telling them, “Why cry over parts of life when the whole it calls for tears?” His words are just as sage now as they were back then. We tend to think of our momentary hardships–even our own forced suicide–as unique and without equal, that no one will ever understand what we’ve gone through. While that’s in some ways true, we have to realize that people, no matter where or when they live, have felt a similar way. Life is, as Buddhists observe, dukkha–not just suffering but impermanent. We are all in a fight against time, and literature, thankfully, freezes that one imperfect moment so we may come back to it again and again.

August 10, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

Lately, I have heard a lot about ideas such as cultural appropriation and cultural exchange, ideas of privilege and oppression, ideas, which, ultimately create a quandary for the artist. Of particular note, has been the increased calls for diversity, both behind the art and in the thing itself. These goals, I believe, are admirable and well within reason. It is largely benign, of neither insult nor disfigurement to American art at large; instead, it is to our shared benefit. We should have a plethora of unique and boisterous voices to admire. Good art is always worth striving for. However, there seems to be strain of these criticisms that seems ill-defined at best, an uncertainty, an inability to articulate exactly what the critic wants. The closest I have to a definitive statement comes from J. A. Micheline’s “Creating Responsibly: Comics Has A Race Problem,” where the author states: “Creating responsibly means looking at how your work may impact people with less structural power than you, looking at whether it reifies larger societal problems in its narrative contents or just by existing at all.” There are a couple of ideas here that I take issue with, ones that don’t necessarily mesh with my ideals of the artist.

Hegel wrote that “art is the sensuous presentation of ideas.” Nowhere is the suggestion that art comes attached with responsibilities. I’m not saying that art doesn’t have the power to shape ideas, but more so, there is often a carefully considered and carefully crafted idea at the heart of every work of art. That overarching theme is given precedence and whatever other points a critic discerns in a work fails to recognize the text’s core. In other words, how can we present evidence of irresponsibility of ideas that are not in play?

This, no doubt, branches out of the structuralist and post-structuralist concepts of binary opposition, and most of all, deconstruction’s emphasis on hierarchical binaries. I no doubt concede that such things exist in every text: love/hate, black/white, masculine/feminine, et cetera. However, the great flaw in this reasoning is that these binaries, even when they arise unconsciously, conclusively state a preference in the whole. Such thinking is a mistake. If we reason that such binary hierarchies exist, why should we conclude that they are unchanging and fixed? Such an idea is impossible, regardless how much or how little the artist invests in their creation. Let’s take a look at a sentence–a tweet, in fact from Roxane Gay–in order to make such generalities concrete:

I’m personally going to start wearing a lion costume when I leave my house so if I get shot, people will care.

We will ignore the I of this statement as it is unnecessary in order to make this point. We have to unpack the binaries at play. First, we note the distinctions in life/death, animals/humans (and also humans/animals). These binaries exist solely inside this shell, yet, if we consider this as a part of a much larger endeavor, we are likely to find contradictory binaries in other sentences. When exactly can we decide the author has concluded? How can we determine the author’s point? Can we ever decide? Now think of applying such an act to a text of 60,000, 80,000, 100,000 words. There’s no doubt it is possible. Yet, should we sit there and count any and every binary that privileges one of the terms? Would that move us any closer to a coherent and definitive message? I find it unlikely.

Of course, I’m not advocating for a return to the principles of New Criticism nor I am saying that post-modern philosophy and gender/race/queer theory have no place in the literary discourse, but to simplify a text, to ignore its argument, seems inherently dishonest. Critics are searching for validation of their own biases, a want to see what they see in society whether real or imagined. This is by no means new, as Phyllis Rackin notes in her book Shakespeare and Women, “One of the most influential modern readings of As You Like It, for instance, Louis Adrian Montrose’s 1981 article, ‘The Place of a Brother,’ proposed to reverse the then prevailing view of the play by arguing that ‘what happens to Orlando at home is not Shakespeare’ contrivance to get him into the forest; what happens to Orlando in the forest is Shakespeare’s contrivance to remedy what has happened to him at home’ (Montrose 1981: 29). Just as Oliver has displaced Orlando…Montrose’s reading displaces Rosalind from her place as the play’s protagonist….” Rackin’s point is clear: If you go searching for your pet issue, you’re bound to find it.

#

I am not fond of polemical statements nor do I want to approach this topic in a slippery-slope fashion as it simplifies a large and complex issue which is too often simplified to fit the writer’s implicit biases. In order to explore thorny or shifting targets such as these, we need to strip away whatever artifice clouds our judgement and consider the assumptions present therein. Unfortunately, most of the discourse has been narrowly focused, boiling down to little more than a sustained shouting contest, a question of who can claim the high ground, who can label the other a racist first. This is not conducive to any dialogue and only serves to make one dig in their trenches more deeply. It is distressing to say the least.

One of the assumptions most critics make goes to the pervasiveness of power, that power is, as Foucault puts it, everywhere, that there is no one institution responsible for oppression, no one figure to point to, but instead, it is diffused and inherent in society. Of course, Foucault’s definition of power is far from definitive and impossible to pin-down. Are we merely subject to the dominance of some cultural hegemony, some ethereal control that dictates without center as some suggest? This, it seems to me, only delegitimizes the individual. Foucault suggests that the subject is an after-effect of power; however, power is not a wave that merely washes over us. It is a constant struggle for supremacy. Imagine it on the smallest scale possible: the interaction of two. Even when one achieves mastery over the other, the subordinate does not relinquish his identity. These two figures will always be two, independent to some degree. The subordinate is relinquishing control not by coercion but by choice. Should the subordinate resist, and he does so simply through being, the balance of power shifts however slightly.

Existence is not a matter of “cogito ergo sum,” but a matter of opposition, that as long as there is an other, we exist.

#

Many people have made the distinction between cultural exchange and cultural appropriation, that the former is a matter of fair and free trade across cultures while the latter is an imposition, a theft of cultural symbols used without respect. While this sounds reasonable, the exchange is impossible.

There is no possibility of fair and equal trade: One will always have power over another.

We assume that American culture is some definable entity, that there is some overall unity to it, but just as deconstructionists demonstrated the unstable undecidability of a text, a culture too is largely undecidable. A culture is not some homogenous mass, but a series of oppositions at play, vying for influence.

We can use myself as an example. Of the categories to which I subscribe or am I assigned, I am a male, cis, white, American, Italian-American, liberal, a writer, an academic, a thinker, a lover of rock n roll, and so on. Each of these cultures are in opposition to something else: male/female, cis/trans, white/black, white/asian, white/hispanic, et cetera. These individual categories form communities based on shared commonalities, but to suggest that these segregating categories can form a cultural default or mainstream is deceptive. Each sphere is distinct from the other, a vast network of connections that ties one individual to a host of others based on one facet. Yet this shared sphere does not create a unified whole. There is no one prevailing paradigm. It is irreducibly complex.

So what’s the point here?

Cultural appropriation, if such a thing exists, is inevitable.

#

It should go without saying, but these ideas of oppression and power are ultimately relative. Depending on what community you venture into and your privilege inside it, you will find yourself in one of these two positions—always. America is as much a text as a novel or any other piece of art. We can count up our spheres of influence, those places we are powerful and those places we are powerless and come no closer to overall meaning.

This is not a call to throw up our hands in nihilistic despair for the artist. The artist would be wise to remember their own power, their ability to draw the world uniquely as they see it. If an artist has an responsibility at all, it is not to worry what part of the binary they are or are not privileging, what hierarchy they summon into being. Someone will always be outraged, oppressed, angered as long as they are looking for something to rage about, regardless of whether it is communicated consciously or not.

Freudian criticism often looks at the things that the author represses in the text, the thoughts and emotions that the author is unwilling to admit explicitly. When asked to give evidence, the critic often claims that the evidence does not need to be demonstrated because it cannot be found: It is somehow hidden. And it is this vein, that sadly, has infected our current approach to texts. We co-opt a text for our own biases, to express what the critic can project onto them, rather than what the work itself describes. We look for any example which might fit our goal and consider it representative of the whole. That is cherry-picking at its most obvious, and an error we should all strive to avoid.

We tend to forget that there are bad texts available to us, that do absolutely advocate the type of propaganda that critics infer in works that approach their subjects with care and grace. How can we scrutinize The Sun Also Rises as antisemitic, as heterosexist, as misogynist when we have books like The Turner Diaries that clearly are? How can we damn Shakespeare for living in a certain era? How can we cast out great works which recognize the complexity of existence and ignore those which undoubtedly make us uneasy?

To the point, we are more enamored by the implicit over the explicit. The central argument of a text is what deserves our attention, how it is made and whether it is successful. We cannot presume to know the tension of other binaries as that text is still being written, constantly shifting, unending in its fluidity.

#

It is easy to make demands on the artist. Anyone can do it. Criticism is one of the few professions that does not require any previous knowledge or qualification. It is, at its heart, an act of determining meaning, and many, I would argue, have been unsuccessful. The hard part is creating meaning. And to those who make some great claim on what art should or should not do, my advice is simple: Shut up and do it yourself, because, by all means, if it’s that easy, demonstrate it.

July 21, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

I think I was twenty-three at the time, having a ginger ale with Kaylie Jones and Nick Mamatas, talking about my favorite books. We went through the list: The Death of Artemio Cruz, Rosa, Rules of Attraction, Notes from Underground, The Great Gatsby, Tell Me a Riddle, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, A Moveable Feast, Portnoy’s Complaint. Mamatas picked up on the theme throughout. It seemed I preferred narratives that had, what he called, “alienated monologues.” After some thought, I realized he was probably right. Not all the books used the techniques, but a fair share of them did. I think what draws me to them is those unique voices, how the the writers create a person out of nothing but words, and they still fascinate me, which is what makes “Here is a Place to Be” by Joseph Graham such a disappointment.

I don’t remember where I read it, maybe Gardner’s Art of Fiction, but there was a comparison of two different first lines from Melville. One was a novel that wasn’t very successful or good, according to the author; the other was from Moby Dick. The lines showcased the importance of establishing a strong voice from the get-go, as Ishamel does in one, simple sentence, compared to the other, which takes several lines to convey almost nothing. “Here is a Place to Be” falls into the latter category: “Todd holds me under.”

I’ll admit that this sentence introduces a problem, an urgent one for the character, but it’s the kind of problem we often find in bad prologues to bad genre novels. It’s meant to create excitement and concern, but how can the reader feel for something he or she knows so little about? Who is being held under water? How did they get here? Why? These questions are raised, but their answers are so delayed, it’s a struggle to reach them. It doesn’t make the story more interesting because we’re not invested. Instead, it feels dishonest, a cheap trick to capture our attention. And what’s worse is that the following sentences fail to clarify much of anything, choosing to focus on the immediate details of the protagonist’s surroundings, descriptions of the water and the muscles of Todd’s forearm like “snakes slithering beneath his skin.” I will give the author credit though. It’s good imagery which befits Todd’s character. It is a shame then that more of that craftsmanship didn’t spill over to the rest of the story.

The body of the narrative is the protagonist’s psuedo-stream-of-consciousness thoughts as he dies in the unknown body of water, where we get a full taste of that “alienated monologue,” and the results are disappointing at best.

The first thing that stands out is the style. It lacks variety. Most of the sentences are around the same length with the average size of about fifteen words long. There are, of course, a few sentences on the beefy side, but on the whole, they mostly look and sound the same. Even in construction the style seems one note. Graham seems only capable of writing typical noun-verb clauses and tries to use conjunctions or fragments to vary the rhythms (though there are a total of three imperatives early on). Graham writes:

I am in the business of forgetting. I am in the business of creating. Todd tells us our whole lives are a work of plagiarism, all of it is derivative. He tells us that there are two ways to make a difference in this world. He says one way just happens to be a whole lot easier than the other. He has us all read Oliver Twist, as if we are his students, his children. He tells us that he is our Fagin. I never read the book so I have no idea what he means.

The repetition and use of parataxis here doesn’t enhance but detracts. Aren’t there other forms of sentences, other rhetorical techniques at your disposal? So why use only one? Now, the case could be made that the prose is meant to feel deadening, as a reflection of the character’s state of mind, and I’ll grant you that. However, I don’t know that anaphora and repotia is the best way to do it. Those first two sentences are meant to be read to together as the reader should notice the repetition, yet Graham uses a period over a colon, which seems like a mistake, making the prose disjointed and cumbersome. Wouldn’t that do a better job establishing their connection? I know it seems nitpicky, but these things are important. They’re the invisible part of writing, what lulls the reader into the fictive dream as they unconsciously process the story’s theme. Here, the style is impeding that process.

Furthermore–and this is far less excusable–the story seems purposely vague. I understand that this is a character study, a portrait of Todd and his little cult of personality, but just because it’s using an irregular form does not mean shouldn’t be crafted for clarity or unity. The details of the narrator’s life in the cult lacks specificity of its events, focusing instead on the insignificant.

For example:

We whisper about his age sometimes. We think he is about forty. He’s got this violent grin, and the minute he meets anyone he can tell exactly what they want and how much they are willing to give in return. He plays jangly pop songs on his electric guitar, flakes of blue paint chipping away from the body of the guitar as he twists and swivels his feet around the compound, singing, a high-pitched squeal. He tells us that he found the guitar in a dumpster behind a church. The guitar is missing two strings now and I remember when he showed me the bodies of the two boys in the back of his trunk. Deep, red lines circling their throats, pale skin. He squeezed my shoulder when I was on my knees vomiting into the toilet. He told me there were only four strings left on the guitar.

Graham is more interested in local color than rendering an accurate and comprehendible idea. When you’re writing in such a limited form, why bother with lengthy descriptions? Furthermore, this cult is so ill-defined. Why exactly does Todd kill these kids? What’s his master plan? We’re really not given the right information here. If the point of the piece is draw Todd as a person, why isn’t he depicted as little more than a slightly benevolent psychopath? Or is it show the types of people who can succumb to such “safety,” like the narrator? Worst of all, the story doesn’t answer any of the questions it raises.

Even the ending is ellipitical and forced. As the narrator drowns, he says, “for the first time in a long time I feel clean.” Why exactly? Because his suffering is over? Because he has graduated as a “Lost Boy”? And what’s with the Oliver Twist reference? Is that supposed to enhance our reading of the text, some insigificant allusion, put there to parallel a similar situation without any of the context to clarify?

This story is a frustrating one to say the least, and I wouldn’t say that’s a good thing. The characters aren’t well-developed here, and the narrative seems needlessly framed by the narrator’s death. Sure, you might say that people are ultimately unknowable, but fiction attempts it nonetheless. The problem with this one is that it doesn’t bother to try.

July 19, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

I was introduced to Spartan via Twitter. I’m not sure how exactly, but I’m glad I was. The magazine’s aesthetic is clean and sparse, both in prose and in design. It’s clear the editors want to put the stories at the fore, and that’s an approach that is much appreciated, not too mention rarer than ever.

One of the stories I read was “Going, Going” by Anton Rose. It’s a slice-of-life, maybe a little over one-thousand words, and for the most part, it’s flash fiction done well. I know I’ve been critical of the form in the past, but this story reminds me that there are people who recognize the strengths of the form, like Rose. The problem with most flash fiction is that it often serves as a good opening to a much fuller and richer story that’s buried beneath a pile of description and exposition and typically forces profoundity onto the unprofound. Most writers of flash fiction subvert the elements of fiction not out of necessity but out of ignorance as they present their trite moments of reflection. “Going, Going,” however, largely succeeds in proving my bias wrong.

At first, it seems as though it’s one man’s struggle with cancer, but quickly, it devolves (in a good way) into something else entirely, tapping into magic realism and surrealist traditions. The twist is a unique one that surprises as much as it excites.

The structure too is pretty smart. Rather than dwell on one scene for its entirety, Rose chooses to use a series of snapshots to depict the enormity of his nameless protagonist’s situation, and though there’s no real sense of cause and effect as they bleed one scene to another, there’s still an overall sense of progression.

Rose’s primary conceit, the loss of hair and appendages, serves as the ticking bomb of the story, creating a sense of dread in the reader as the protagonist nears closer and closer to nothingness.

The prose has a Kafkaesque flair to it, not necessarily in the length of sentences or the complexity of their construction, but the flatness with which the narration presents the character’s situation.

He was sitting on the toilet one afternoon when he felt an itch at the tips of his toes. He pulled his feet out of his socks and shoes so he could scratch them, but his toes weren’t there anymore. He checked his socks, but they were empty.

There’s an uncanny aura to everything, as the reader is denied access to the protagonist’s thoughts and feelings. We are left to our own devices and wonder if the character is disturbed by his metamorphosis as much as we are.

The nameless protagonist seems purposeful too. I think Rose wanted him to be a everyman-type character, one whose situation is relatable to anyone, a physical manifestation of the human condition. Rarely, does the protagonist react with horror or shock but, instead, with bemused indifference, recognizing the inevitablity of his fate, even as he watches others around him disappear:

A couple of days later he was sitting in the clinic again. The guy who normally sat to his right wasn’t there. Hadn’t been there for a while, now he thought about it. He tried to remember the man’s name, but he couldn’t bring it to mind. He only saw the chair, empty.

It’s a beautiful piece, even if a bit depressing, executed with a subtle grace. And even though it’s short, it still abides the governing laws of story. It has the structural elements we expect from fiction and succeeds in using them: It just uses a unique form to express them–which I think is what we should all strive for as writers. Experimentation is important, but it should never come at the cost of the story. They are one and the same, a part of a whole that must be manipulated as a choice, not a mistake.

Unfortunately, this story isn’t perfect, but few rarely are. The last scene feels like a missed oppurtunity, where the protagonist strips in the park and “melts” in the sunlight. I’m not sure what to make of it. There’s a sense of acceptance in the description, but we never had any real resistance earlier, making the character’s transformation seem dishonest and not earned. Furthermore, I think that last scene probably should have been the story’s fullest, rather than its most slight, and I’d probably attribute that to the story’s lack of interior. The narration is so distant throughout, and this is a place where that change would be justified and appropriate. It would enhance the overall thematic argument. I’m not saying that I don’t like the subtlety of the story–in fact, it’s one of its strengths–but sometimes that subtlety makes things more opaque than clear.

So other than those two minor flaws, this is a very good short story and well worth your time. And most importantly, it reminds us that there are writers who still partake in the tradition, even as they actively revolt against it.

July 17, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

It seems that the loudest voices in our most important communities are the ones who value hyperbole and polemism more than naunce and reason. They choose not to elaborate or explain. They believe their points are self-evident and beyond reproach, protected by the type of progressivism we all aspire to. That is not to say there aren’t any reasonable, intelligent people who deal with these issues. (If you need an example of thoughtful conversation, listen to Our National Conversation About Our Conversations About Race Podcast.) But anymore, the outrageous stand out, and when you look at their arguments, it becomes clear that they’d rather claim something to be true than prove it.

I was recently introduced to one of our latest cultural debates by Roxane Gay, editor of Pank, from Twitter. She wrote: “That NY Times article on Serena’s body is so misguided and racist and utter trash.” Now, obviously, Twitter isn’t a great space for proving arguments, but very few people have taken a greater space online or in print to explain. Maybe I’m an idiot, but I like I need evidence to be convinced, not empty claims. Again, most of the outcry has come from Twitter, but there have been a few that have eeked out that look exclusively at the article.

Maybe we should begin with the article in question, “Tennis’s Top Women Balance Body Image With Ambition” by Ben Rothenberg. Let’s put it under the microscope and look for racism and sexism, since it should be pretty easy to find.

The article begins with a description of how Serena Williams blends into the crowd: long sleeves. This first line doesn’t do a good job of making Williams an “other”–at least racially. (It doesn’t even bother to mention her race or the race of any other players for that matter.) The implication here isn’t that her body is all that different. If she can hide who she is by hiding her arms, shouldn’t that raise a question: Is her physique being portrayed as that “manly” or “masculine”? That seems unlikely. What is being suggested is her definition is “masculine,” according to other players, not the author. And if we approach this in a biological sense, instead of an emotional one, we can begin to understand what is the “problem”: musclarity.

Let’s be honest, women are afraid of muscles for the most part. If you were to go to any gym, you’ll find almost all the women working out on the treadmill or maybe doing some bodyweight exercises. And if you ask them why, they’ll respond that they don’t want to get “big,” that they want to “stay a woman.” People think that touching a weight turns you into a bodybuilder, that by benching or deadlifting, you’ll look like Ms. Olympia. People tend to forget that those people eat a lot more than any of us ever will and pop steroids like they’re fucking smarties.

One of the most quoted lines in the article is “Williams…has large biceps and a mold-breaking muscular frame, which packs the power and athleticism that have dominated women’s tennis for years. Her rivals could try to emulate her physique, but most of them choose not to.”

That does create a binary, I will admit that, but not the one people are so quick to offer. It’s sugesting that the reason why Serena Williams is so good at tennis is that she has the musclarity to be good, and there’s a reason her competitors can’t keep up. They think, like most women in the gym, that muscles equal masculine.

Take a look at the following quote for further evidence:

“It’s our decision to keep her as the smallest player in the top 10,” said Tomasz Wiktorowski, the coach of Agnieszka Radwanska, who is listed at 5 feet 8 and 123 pounds. “Because, first of all she’s a woman, and she wants to be a woman.”

Radwanska, who struggled this year before a run to the Wimbledon semifinals, said that any gain in muscle could hurt her trademark speed and finesse, but she also acknowledged that how she looked mattered to her.

“Of course I care about that as well, because I’m a girl,” Radwanska said. “But I also have the genes where I don’t know what I have to do to get bigger, because it’s just not going anywhere.”

Look at the contrast between the first paragraph here and the second. Notice anything? In the first paragraph, Radwanska’s coach explains that “she’s a woman, and she wants to be a woman.” What follows immediately is a rebuke of such a statement. Radwanska wasn’t as good as she could have been because she worried about her appearance. That’s a pretty good use of juxatoposition, I’d say. Of course, this does validate some of those arguments for this idea that Williams is more “masculine.” However, the next few paragraphs puts that idea in question.

For many, perceived ideal feminine body type can seem at odds with the best physique for tennis success. Andrea Petkovic, a German ranked 14th, said she particularly loathed seeing pictures of herself hitting two-handed backhands, when her arm muscles appear the most bulging.

“I just feel unfeminine,” she said. “I don’t know — it’s probably that I’m self-conscious about what people might say. It’s stupid, but it’s insecurities that every woman has, I think. I definitely have them and I’m not ashamed to admit it. I would love to be a confident player that is proud of her body. Women, when we grow up we’ve been judged more, our physicality is judged more, and it makes us self-conscious.”

This section presents this masculine/feminine binary as a sophmoric belief. For one, it holds players back. And two, players, like Petkovic, recognize the absurdity of it. She’s too concerned with what others will think to win.

She even says, “I feel like there are 80 million people in Germany who think I’m a bodybuilder. Then, when they see me in person, they think I’m O.K.”

Again, this is a mistake people are making, confusing definition with masculinity. Yes, men have less essential fat on their bodies than women. That we cannot debate. But defining body fat percentage as a masculine/feminine idea seems counterproductive and unfair, which is how the public–and many of the players–see it.

The following paragraph even goes on to show the problems with such a distinction.

Williams, 33, who has appeared on the cover of Vogue, is regarded as symbol of beauty by many women. But she has also been gawked at and mocked throughout her career, and she said growing confident and secure in her build was a long process.

First, let’s recognize that the article explains that their are people who find Williams to be both beautiful and ugly–but Williams is “confident and secure,” regardless of the haters. If anything, this article is shaping up to have a theme of acceptance and empowerment than one that is racist and/or sexist.

The author even writes that “Not all players have achieved Williams’s self-acceptance.” The argument emerging is clear: The reason Wiliams is great is because she accepts who she is and, more importantly, does whatever is necessary to improve.

There are even a couple of quotes that further that argument: “‘The way Serena wears her body type I think is perfect,’ Shriver said. ‘I think it’s wonderful, her pride.’” Or: ““I actually like looking strong,” Watson said. “I find strong, fit women a lot more attractive than lanky no-shape ones.” Or: “‘Right now I’m a tennis player, so I’m going to do everything I can to be the best tennis player that I can be,’” said Wozniacki, who was featured in the Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue last year. ‘If that means that I need to add a little muscle to my legs or my butt or whatever, then that’s what I’m going to do. I can be a model after I finish.’” Or: “‘If I’m getting bigger, then I’m getting bigger,’” Bacsinszky, 26, said, adding, ‘I know if it’s for my sport, and the good of my forehand and my backhand and my serve, then I will do it.’”

Quotes like those certainly draw a line, and that line is clearly in favor of acceptance and improvement.

The article even ends with an appreciation of strong, musclar arms, the very thing Williams was hiding from the article’s outset:

Eugenie Bouchard, who was often dubbed “the next Maria Sharapova” as she ascended the rankings last year, said she hoped to gain more strength and muscle as her results have fallen off.

“If I start to see it, I’ll be happy,” Bouchard said. “If it’s what you need to lift trophies, who cares what you look like?”

That too me sounds pretty empowering. And even though it’s journalism, meant to only give the facts, there seems to be a sense of narrative, an artisty to the construction. It abides the laws of good fiction as much as it does good essays.

So what are the counter arguments?

In “Women’s Sports and Sexism: Isn’t Serena Williams Winning Wimbledon Enough?” by Teresa Jusino, there isn’t too much evidence presented, only a gut feeling, a sense of what the reader feels rather than what is on the page.

The article starts by injecting as much charged language as possible,. The article suggests that the very premise of “Tennis’s Top Women” “pits women in a field against each other,” which is “misogynist,” and “operates under the false assumption that only men can be muscular, and so muscular women are ‘masculine’ aberrations deserving of scrutiny.”

I think this misses the point entirely. First, what is narrative without conflict? Boring. And so what if women are “pitted against each other,” isn’t that the whole point of women’s tennis? Is the comparison of physiques now an affront to women? Isn’t that what people do, whether we admit it or not? We’re going to look at things we like more than things we do not. This seems like a over-simplistic assumption, at best. Furthermore, the article is presenting other people’s false assumptions. Some players believe that muscularity is inherently masculine, as shown in the quotes by some of the players, but whether Williams believes that or not is not the point: She accepts who she is. She is happy with her physique. It is defined not by others, but by her ability and confidence. Even better, where does the article say, explicitly that this is the case, that it is starting with this assumption? Or is Jusino injecting her own personal bias into her reading?

Soon after, Jusino states:

The very idea of this article is steeped in sexism. It would be one thing if you were interviewing a female tennis player and the issue of body image came up in conversation. It’s quite another to make that the story and ask female athletes at the top of their games whether or not they like “looking muscular;” [sic] covering it as if this is a timely story and a new trend in sports. NEWS FLASH: Women are judged on their bodies wherever they fucking go. They don’t need news stories to reinforce that.

This statement is problematic for a number reasons. First, it assumes there’s a context within which discussing body image is appropriate for journalism, and that an entire story devoted to the issue is not that context. Two, that because women are judged on their bodies, we don’t need additional reportage that confirms that women are judged on their bodies. That seems like a very unwise statement to make. Just because a story confirms something that bothers us doesn’t mean that we should never report it. Isn’t that a bt more meta than the typical fashion/gossip magazine perspective? But that’s problem when people, presumably, don’t read all the way through or closely enough.

“Tennis’s Top Women” presents a very Joycean argument, where “The artist, like the God of the creation, remains within or behind or beyond or above his handiwork, invisible, refined out of existence, indifferent, paring his fingernails.” And Rothenberg is letting the players make his argument for him.

But this is the age we live in. Critics read their own biases into texts and repurpose them in order to further their own cause, regardless whether their argument about the text is valid or not. They see things that they want to see. I’m about as liberal as they come, but this kind of approach really turns me off. I can sympathize with those who see things the other way because the most important voices in our field tend to be the most irrational and illogical. As critics, we should make it our utmost priority to mine texts for what is being communicated. I’m not saying we need to go back to the days of the artist as sole interpreter of the text, but we do need to start casting off the chains of these cultural critical lenses. They’ve done a lot of good–there’s no doubt–but when we start to criticize a text for what’s unsaid as much as what is said, we start to alienate the very people we agree with.

July 16, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

“Cardboard Graceland” evidences many of the problems found in trendy short fiction. It’s replete with pop culture references and has an aimless plot that owes as much to its form as it does to its unclear direction and lack of narrative drive. Even the story’s first line isn’t all that appealing or interesting. Yes, it creates a problem for the character, but the conflict is buried, lost under the wave of description. Furthermore, Fogarty doesn’t use the basement in any meaningful way. He could let it serve double-duty to make the setting an extension of the character, to represent something about the narrator, but the prose is so flat and lifeless that any metaphorical parallels can’t be drawn by the reader. Just look at the following lines, where he writes: “I found a can of gold paint on sale and took it to a couple of the walls. Tacked up some of my old records and my velvet Elvis. Made it feel like home.” Moreover, the use of fragments here serves no discernible purpose. Why that over a comma? Maybe that last sentence could stand as is to emphasize the narrator’s “home,” but tacking up records does not require careful scrutiny on the part of the reader. It is a careless and unnecessary choice that seems thoughtless at best.

The narrator then tells us his proudest accomplishment: He found a bunch of cardboard boxes outside a mall and turned them into Graceland. This reeks of the typical quirk wedged into bad fiction. The reason why it doesn’t work is because it doesn’t have any baring on the narrative or the theme (whatever that may be). When you look at examples of absurd quests, in the Pynchon sense of the phrase, the author typically uses the absurdity in a way that demonstrate the futility of the the protagonist’s, and by extension our, goals. Here, instead, it serves only as useless exposition, which the author can’t seem to give enough of. This seems to be a constant throughout the story too.

It isn’t until paragraph nine that we actually get a sense of plot, something besides the expositional onslaught. In paragraph ten, we get a real scene, but this seems rushed rather than the dramatic crux of everything we’ve read so far:

So this afternoon I trimmed my burns and pulled on the jumpsuit and I went to the Boardwalk. It’d been raining. The air was hot and humid and I was sweating and the wet shorted one of my amps, cut out the sound halfway through my entrance music. I tried to do my big karate kick, but the seams on my suit split under the arms and I had to stop. There weren’t many people out except for some teenagers, surf kids probably, and they stopped whatever they were doing to watch and laugh. I’ve got a wireless mic that lets me roam a bit and work the crowd and since they were my only crowd I tried to banter. Asked where they were from. They laughed and one of them called me a fat old loser and another one called me the worst Elvis he’d ever seen. Tall blonde kid with a backwards baseball cap said I was a faggot with bitch tits.

Forgarty shows his narrator failing, which I will say we would expect at this point considering what we’ve heard prior, but there’s no real weight to it because we’ve never seen the narrator try before. We’re told that his “Hound Dog” is better than Elvis’s, but we aren’t shown it. Wouldn’t it have been better to start with his “success,” even a glimpse of it, so when the fall comes, we can be a bit more empathetic?

By the story’s end, the narrator “dies” just like Elvis, but there’s no sense of closure or finality to it. It feels as though the story just stops, and the writer is unsure why. Furthermore, what feeling should the reader walk away with? Is this a genius who the world doesn’t appreciate or a washed-up never-was? The narrator certainly doesn’t give us any indication of what he is. And I don’t think that enhances the story either. Sure, we could debate what the narrator was or was not, but without some direction from the narrative, we’re left to wonder if the problem is with the world or with the narrator.

One last thing, “Cardboard Graceland” has a structure that is unusual—to be polite about it. It’s a series of descriptions that leads to a climax and resolution, but the rest of its building blocks are largely absent. What events led to the narrator’s final performance? We know he’s a fat Elvis now, but we don’t know what makes him decide to give it one last go. We need some kind of inciting incident to chart his course. In short, there’s a lack of causality that makes the story as a whole seem frustrating rather than enlightening. So really, why should a reader spend his or her time on this story when there are so many more out there?

July 14, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

Nick Gregorio’s “Goings-Ons and Happenstance” really shouldn’t be as good as it is. A story like this, with an opening like that, could have quickly veered into Lifetime territory. That’s not to say that the first line isn’t a good hook—it introduces the conflict, gives the protagonist a problem, and pulls in the reader, so it is—but how many terrible stories open with such a situation? But fortunately, Gregorio’s care and grace as a writer shines through his prose and avoids any sense of trite sentimentality. It’s obvious in the way he melds memories of the incident into memories of the nameless protagonist’s life, slyly introducing exposition without dumping on the reader. He writes:

[S]he couldn’t remember if she’d ever noticed how pock-marked those flat cheeks of his were. Craggy and white, it reminded her of when she was a teenager, of what her own bare ass must have looked like pressed against the passenger window as she and her friends drove past movie theater marquees

The use of juxtaposition here, to contrast what she thought she knew with what she does know, creates an aura of uncertainty, a feeling of conflict even when doing something as simple as giving backstory to the reader. It’s the hallmark of genuine talent. Most writers fail to recognize that exposition is boring. It should parceled out and delivered naturally, typically with something else that pushes the narrative forward.

Even Gregorio’s use of summary is thoughtful. Instead of simply telling us that the protagonist is in a bad place or that she feels lost, he shows us with a meaningful string of snapshots:

She said, “Never thought of it that way,” sitting at the dinner table, staring at the food she hadn’t touched, at the phone that was spinning on its own axis as it vibrated from the calls she wasn’t picking up. The sound it made on the table reminded her of the garage door opening, of his coming home from work. But the front door never opened. And she sat there until she went and curled herself up on the couch.

In the morning, Friday, she counted Jim’s missed calls. She waited until lunch to listen to his voicemails. They were composed at first, almost professional.

Gregorio’s style here is also important to note. Rarely is there a wasted word. There are some occasions were the language could be a better little, like when he writes “Before then she’d never seen what his ass looked like in that set of circumstances,” which probably could have been shortened to just “in that circumstance,” but overall, his minimalism, both in language and in scene, is one of his strengths as a writer. He uses understatement effectively as well, with lines like, “she’d watched for a minute. Not because she was turned on, that would’ve been ridiculous.” The writer clearly has a sense of humor. Even his use of fragments is careful and considerate. A lot of writers litter the page with fragments because they think it creates a certain “flow,” but often times, it makes the writing monotonous and stale. They aren’t giving enough attention to why, but Gregorio uses his fragments judiciously, punctuating certain lines to highlight something important. (Besides, if a writer uses the same effect over and over, that effect will eventually lose its significance through overuse alone.) When he writes, “Then she remembered having his hand down her pants in that lot. Years ago,” the fragment emphasizes that lost past, drawing a line between the then and the now. We as readers understand the protagonist’s trajectory in the scene before it even happens. We recognize, through style, that this won’t be a friendly meaning. She’s not going to embrace Jim with open arms, and all of that is communicated with the smart use of a period.